A pocket full of water molecules

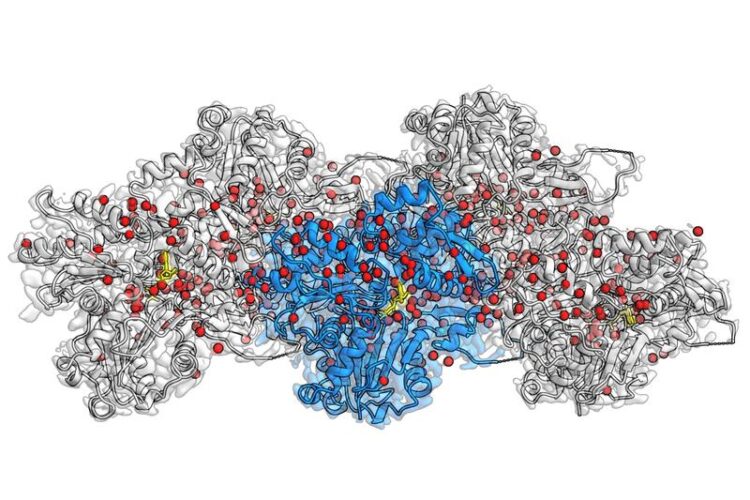

Cryo-EM reconstruction of F-actin bound to Mg2+-ADP-BeF3. at 2.2 Å resolution. The central actin subunit is colored blue, the other four subunits are grey. Densities corresponding to water molecules are colored red and ADP in yellow.

(c) MPI of Molecular Physiology

– how actin filaments drive the cell’s motion.

Actin filaments are protein fibers that make up the internal skeleton of the cell. They support cellular processes like the cell’s fusion and are also a major constituent of muscle cells. For the first time, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology in Dortmund, Germany, have been successfully able to visualize hundreds of water molecules in the actin filament. Using the technique of electron cryo microscopy (cryo-EM), Stefan Raunser’ group reveals in unprecedented detail how actin proteins are arranged together in a filament, how ATP – the cell’s energy source – sits in the protein pocket, and where individual water molecules position themselves and react with ATP.

“We are answering fundamental questions of life that scientists have been trying to answer for several decades”, remarks Raunser. In eukaryotic cells, actin proteins are abundant and tend to join together (polymerize) into filaments. These filaments make up the network that constitutes the cytoskeleton of the cell and controls various cell processes through movement. Immune cells, for example, use actin filaments to move and hunt bacteria and viruses. Researchers knew already that the filaments’ dynamics is regulated by ATP hydrolysis – the reaction of ATP with water that cleaves a phosphate group and generates energy. What previously remained unanswered, however, was the exact molecular details behind this process.

Too flexible, too big? – not for cryo-EM

As actin filaments are too flexible or too big for X-ray crystallization and nuclear magnetic resonance, cryo-EM has been the only technique viable for obtaining detailed images. In 2015, Raunser’s team used cryo-EM to picture a novel three-dimensional atomic model of the filaments, with a resolution of 0.37 nanometres. In 2018, his group described the three different states that actin proteins acquire in the filament: bound to ATP, bound to ADP in the presence of the cleaved phosphate, bound to ADP after release of the phosphate.

How water molecules move

In their current study, Raunser and his colleagues were able to set a new resolution record: they obtained all three actin-states with a resolution of about 0.2 nanometers, making previously invisible details visible. The three-dimensional maps not only display all amino-acid sidechains of the proteins but also reveal where hundreds of water molecules are placed. Through comparison between these new structures and those of isolated actin, they were able to infer how water molecules move. Upon polymerization, water molecules relocate in the ATP pocket in such a way, that only a single water molecule remains in front of ATP, ready to attack one phosphate and initiate hydrolysis. The accuracy obtained through this approach can help further research in the field: “Our high-resolution model can propel scientists in designing small molecules for light microscopy research on tissues, and ultimately in therapeutic applications”, Raunser says.

A door opener!?

The authors also cast light on the final fate of the phosphate. Previously, scientists believed there to be a back door in the ATP pocket that remains open after ATP hydrolysis to facilitate the exit of the phosphate. However, the new cryo-EM structures show no trace of open backdoors. Hence, the release mechanism remains a mystery. “We believe there to be a door, but it likely opens momentarily”, comments Raunser, who now wants to use mathematical simulations and time-resolved cryo-EM methods to demonstrate just how the phosphate exits. Evidently, these exciting discoveries have opened the door for scientists to dig deeper in the hopes of discovering even more details behind the processes by which actin filaments contribute to the cell’s motion.

Wissenschaftliche Ansprechpartner:

Prof. Dr. Stefan Raunser

Max Planck Institute of Molecular Physiology

Tel.: +49 231 133 2300

email: Stefan.Raunser@mpi-dortmund.mpg.de

Originalpublikation:

Oosterheert W, Klink B. U, Belyy A, Pospich S, Raunser S (2022). Structural Basis of actin filament assembly and aging. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05241-8

Weitere Informationen:

https://www.mpi-dortmund.mpg.de/news/raunser-nature-actin-water

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…