Early hominids may have behaved more "human" than we had thought

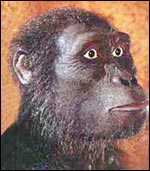

Australopithecus afarensis

Our earliest ancestors probably behaved in a much more “human” way than most scientists have previously thought, according to a recent study that looked at early hominid fossils from Ethiopia

Previously skeptical, an Ohio State University anthropologist now supports the idea that the minimal size differences between male and female pre-hominids suggest that they lived in a more cooperative and less competitive society.

The evidence centers on the extent of sexual dimorphism – differences in size based on sex — that existed among these early primates and what it suggests about the social structure of these creatures.

In a paper published in the August 5 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers at Kent State University reported that remains of both male and female specimens of Australopithecus afarensis showed fewer differences based on size than most paleontologists had earlier expected.

After comparing these bones with the near-complete skeletons of the fossil “Lucy,” the researchers argue that the social structure of our earliest ancestors compared more to that of modern humans and chimpanzees than it does to gorillas and orangutans, as had previously been thought.

Gorillas, orangutans and baboons are known to have social structures built around fierce competition among males. Chimps and humans however, while still competitive, are more cooperative, giving them a greater degree of “humanness.”

In a commentary in the journal, Clark Spencer Larsen, distinguished professor and chair of anthropology at Ohio State, argued that the Kent State study was the best to date at linking sexual dimorphism in early hominids to their probable social structure.

“These researchers have been able to show convincingly that, from the fossil remains, there was very little sexual dimorphism in these early hominids,” Larsen said. “From that, I think we can extrapolate some behaviors – specifically that males were cooperating more than they were competing among themselves – a distinctly ‘human’ behavior.”

Larsen believes that this male cooperation is the product of evolutionary change. “The success of this cooperation proved valuable to these early ancestors and has become a trait among humans,” he said.

Paleontologists knew that there were minimal size differences between males and females since Homo sapiens evolved but the fossil record is so sparse, they were unsure of whether pre-Homo species showed more of less sexual dimorphism. Modern humans show no more than 15 percent size difference on average, Larsen said.

This new study, however, took advantage of a novel fossil find at Site 333 in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia where remains of 13 individuals were discovered in 1975. Scientists believe that they all died at the same time, giving a possible “snapshot” view of how they lived.

Using the “Lucy” skeleton from a nearby site as a template, the Kent State researchers were able to use femur “head” size as a key to extrapolate the size of the individuals from Site 333.

“Only in the last few years have we realized that an individual’s femur head size is a good proxy for its body weight,” Larsen said.

The comparison showed that the sex-based size differences among the fossils at Site 333 were no greater than those for modern humans, suggesting that the same kind of modern social structure with cooperating males also occurred in the days of Australopithecus afarensis.

“I think what we are seeing here are the very first glimpses of ‘humanness’ in these early hominids dating back 3 million to 4 million years,” he said.

Contact: Clark Spencer Larsen, +1-614-292-4117, mailto: larsen.53@osu.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.osu.eduAll latest news from the category: Interdisciplinary Research

News and developments from the field of interdisciplinary research.

Among other topics, you can find stimulating reports and articles related to microsystems, emotions research, futures research and stratospheric research.

Newest articles

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…

Decisive breakthrough for battery production

Storing and utilising energy with innovative sulphur-based cathodes. HU research team develops foundations for sustainable battery technology Electric vehicles and portable electronic devices such as laptops and mobile phones are…

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…