Purdue researchers create device that detects mass of a single virus particle

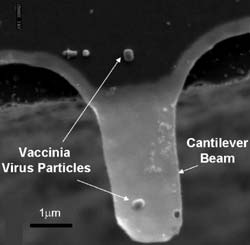

This photo, taken with a scanning electron microscope, shows a miniature "cantilever," a diving board-like beam of silicon that researchers at Purdue University have used to detect a single virus particle weighing about one-trillionth as much as a grain of rice. The work, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is aimed at developing advanced sensors capable of detecting airborne viruses, bacteria and other contaminants. Such sensors will have applications in areas including environmental health monitoring in hospitals and homeland security. (School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Purdue University) <br>

Researchers at Purdue University have developed a miniature device sensitive enough to detect a single virus particle, an advancement that could have many applications, including environmental-health monitoring and homeland security.

The device is a tiny “cantilever,” a diving board-like beam of silicon that naturally vibrates at a specific frequency. When a virus particle weighing about one-trillionth as much as a grain of rice lands on the cantilever, it vibrates at a different frequency, which was measured by the Purdue researchers.

“Because this cantilever is very small, it is extremely sensitive to added mass, such as the addition of even a single virus particle,” said Rashid Bashir, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and biomedical engineering.

Findings are detailed in a paper to appear next month in Applied Physics Letters, a journal published by the American Institute of Physics. The paper, which is likely to appear in the weekly journal’s March 8 issue, was written by doctoral student Amit Gupta, senior research scientist Demir Akin and Bashir, all in Purdue’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The work, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is aimed at developing advanced sensors capable of detecting airborne viruses, bacteria and other contaminants. Such sensors will have applications in areas including environmental-health monitoring in hospitals and homeland security.

“This work is particularly important because it demonstrates the sensitivity to detect a single virus particle,” Gupta said. “Also, the device can allow us to detect whole, intact virus particles in real time. Currently available biosensing systems for deadly agents require that the DNA first be extracted from the agents, and then it is the DNA that is detected.”

The next step will be to coat a cantilever with the antibodies for a specific virus, meaning only those virus particles would stick to the device. Coating the cantilevers with antibodies that attract certain viruses could make it possible to create detectors sensitive to specific pathogens.

“The long-term goal is to make a device that measures the capture of particles in real time as air flows over a detector,” Bashir said.

Scientists are striving to create “lab-on-a-chip” technologies in which miniature sensors perform essentially the same functions now requiring bulky laboratory equipment, saving time, energy and materials.

Thousands of the cantilevers can be fabricated on a 1-square-centimeter chip, Akin said.

The Purdue researchers used the device to detect a particle of the vaccinia virus, which is a member of the Poxviridae family and forms the basis for the smallpox vaccine.

The cantilever is about one micron wide – or about one-hundredth the width of a human hair – 4 microns long and 30 nanometers thick. A nanometer is a billionth of a meter, or roughly the length of 10 hydrogen atoms strung together.

“This cantilever mechanically resonates at a natural frequency, just like anything that vibrates has a natural frequency,” Bashir said. “What we do is measure the natural frequency of the cantilever, which is a function of its mass. As you increase the mass, the frequency decreases. And the way to increase the sensitivity is to make that starting mass very, very small.”

A single vaccinia virus particle weighs about 9 femtograms, or quadrillionths of a gram.

“So, if a grain of rice weighs a couple of milligrams, one of these virus particles weighs about one-trillionth as much,” Bashir said.

Because the cantilevers are mechanical parts measured primarily on the scale of microns, or millionths of a meter, they are called “micromechanical devices.”

The researchers created the cantilever using the same technology used by the semiconductor industry to etch circuits in electronic chips. Silicon is deposited as a blanket onto the surface of a wafer and then formed into patterns during numerous steps, including chemical etching. In this case, a cantilever is formed instead of a circuit.

In addition to funding from NIH, facilities in Purdue’s Birck Nanotechnology Center were used to carry out the experiments.

Writer: Emil Venere, (765) 494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Sources: Rashid Bashir, (765) 496-6229, bashir@ecn.purdue.edu

Amit Gupta, agupta@shay.ecn.purdue.edu

Demir Akin, da@purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://news.uns.purdue.edu/html4ever/2004/040204.Bashir.virus.htmlAll latest news from the category: Process Engineering

This special field revolves around processes for modifying material properties (milling, cooling), composition (filtration, distillation) and type (oxidation, hydration).

Valuable information is available on a broad range of technologies including material separation, laser processes, measuring techniques and robot engineering in addition to testing methods and coating and materials analysis processes.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…