Star-formation like there is no tomorrow: NGC 253 and the limits to galactic growth

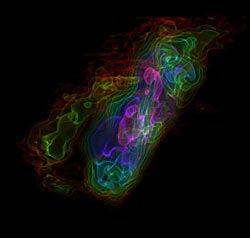

False-color visualization of the data collected by ALMA of the starburst galaxy NGC 253. The color encodes information about the intensity of light received from the gas, from fainter light shown blue to brighter radiation in red. This and similar visualizations helped the astronomers to identify the molecular outflow emerging from the central starburst in this galaxy. This image is the cover image of the July 25, 2013 issue of the journal Nature. Credit: E. Rosolowsky (University of Alberta)<br>

Now, a group of astronomers that includes Fabian Walter from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy were able to obtain the first detailed images of this type of self-limiting galactic behavior: an outflow of molecular gas, the raw material needed for star formation, that is coming from star-forming regions in the Sculptor Galaxy (NGC 253).

The study, which uses the newly commissioned telescope array ALMA in Chile, is published in the journal Nature on July 25, 2013.

Galaxies – systems that contain up to hundreds of billions of stars, like our own Milky Way galaxy – are the basic building blocks of the cosmos. One ambitious goal of contemporary astronomy is to understand the way that galaxies evolve from the first proto-galaxies shortly after the big bang to the present. A key question concerns star formation: what determines the number of new stars that will form in a galaxy?

A key ingredient of current models of galaxy evolution are mechanisms by which ongoing star formation can actually inhibit future star formation: When new stars are formed, a certain fraction of them are very massive. Massive stars shine brightly, and their intense radiation drives “stellar winds”, outflows of gas and plasma that can be sufficiently strong to push gas out of the galaxy altogether. Also, massive stars end their comparatively brief lives in spectacular explosions (supernovae), flinging their outer shells – and any additional material that might be in their way – out into space. Consequently intensive star formation, known as a “starburst”, and the resulting formation of many massive stars, can hamper the growth of future generations of stars. After all, molecular gas that has been flung out of a galaxy cannot serve as raw material from which to fashion that galaxy's new stars. There is a limit to galactic growth.

So far, so good – but what was missing was direct observational evidence for starbursts producing outflows of molecular gas. Until now, that is, when a team of astronomers led by Alberto Bolatto from the University of Maryland at College Park observed the starburst galaxy NGC 253.

NGC 253, also known as the “Sculptor Galaxy”, is a spiral galaxy located in the constellation Sculptor in the Southern sky. With a distance of 11 million light-years it is one of our closer intergalactic neighbors and the closest starburst galaxy visible from the southern hemisphere. Using the compound telescope ALMA the astronomers targeted the central regions of NGC 253, where the most intense production of new stars takes place, and found a telltale outflow of molecular gas at right angles to the galactic disk.

Bolatto, who is the lead author of the study now appearing in the journal Nature, concludes: “The amount of gas we measure gives us very good evidence that some growing galaxies spew out more gas than they take in.” Indeed, the astronomers estimate that each year the galaxy ejects gas with a total mass of nine times that of our Sun. This ejected mass is about three times larger than the total mass of all stars produced by NGC 253 each year (which, in turn, is several times larger than the mass of all stars produced in our home galaxy, the Milky Way, each year).

Fabian Walter from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, a co-author of the study, adds: “For me, this is a prime example of how new instruments shape the future of astronomy. We have been studying the starburst region of NGC 253 and other nearby starburst galaxies for almost ten years. But before ALMA, we had no chance to see such details.” The study used an early configuration of ALMA with only 16 antennas. “It's exciting to think what the complete ALMA with 66 antennas will show for this kind of outflow!” adds Walter.

Contact information

Fabian Walter (co-author)

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

Heidelberg, Germany

Phone: (+49|0) 6221 – 528 225

Email: walter@mpia.de

Markus Pössel (press officer)

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

Heidelberg, Germany

Phone: (+49|0) 6221 – 528 261

Email: pr@mpia.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…