Particle billiards with three players

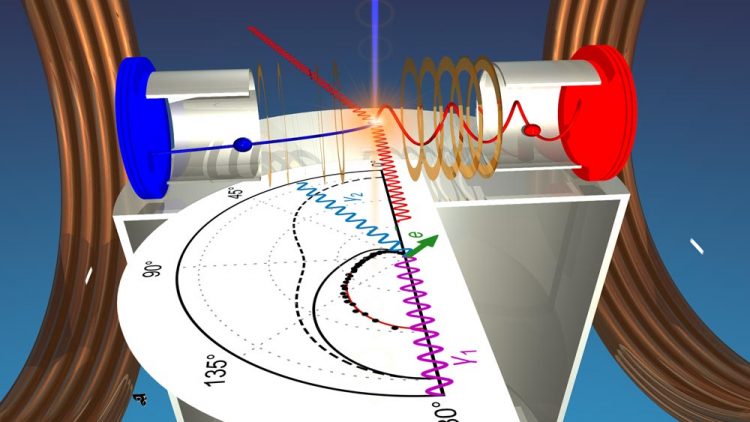

Artist view of the process and cross section for Compton scattering (front) and the COLTRIMS reaction microscope which enabled the experiment (back). Photons (wiggly line) hit an electron in the atom in the centre of the COLTRIMS reaction microscope knocking out an electron (red ball) and leaving an ion (blue ball) behind. Both particles are guided by electric and magnetic fields toward detectors (red and blue discs.) Copyright: Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

Light can be used to knock electrons out of atoms, with light particles and electrons bouncing off each other like two billiard balls – Compton scattering. Why electrons can even be ejected from an atom when the light does not actually have enough energy to do so has now been discovered by a team of physicists headed by researchers from Goethe University Frankfurt. (Nature Physics, DOI 10.1038/s41567-020-0880-2)

When the American physicist Arthur Compton discovered that light waves behave like particles in 1922, and could knock electrons out of atoms during an impact experiment, it was a milestone for quantum mechanics.

Five years later, Compton received the Nobel Prize for this discovery. Compton used very shortwave light with high energy for his experiment, which enabled him to neglect the binding energy of the electron to the atomic nucleus. Compton simply assumed for his calculations that the electron rested freely in space.

During the following 90 years up to the present, numerous experiments and calculations have been carried out with regard to Compton scattering that continually revealed asymmetries and posed riddles.

For example, it was observed that in certain experiments energy seemed to be lost when the motion energy of the electrons and light particles (photons) after the collision were compared with the energy of the photons before the collision.

Since energy cannot simply disappear, it was assumed that in these cases, contrary to Compton’s simplified assumption, the influence of the nucleus on the photon-electron collision could not be neglected.

For the first time in an impact experiment with photons, a team of physicists led by Professor Reinhard Dörner and doctoral candidate Max Kircher at Goethe University Frankfurt have now simultaneously observed the ejected electrons and the motion of the nucleus.

To do so, they irradiated helium atoms with X-rays from the X-ray source PETRA III at the Hamburg accelerator facility DESY. They detected the ejected electrons and the charged rest of the atom (ions) in a COLTRIMS reaction microscope, an apparatus that Dörner helped develop and which is able to make ultrafast reactive processes in atoms and molecules visible.

The results were surprising. First, the scientists observed that the energy of the scattering photons was of course conserved and was partially transferred to a motion of the nucleus (more precisely: the ion).

Moreover, they also observed that an electron is sometimes knocked out of the nucleus when the energy of the colliding photon is actually too low to overcome the binding energy of the electron to the nucleus. Overall, the electron was only ejected in the direction one would expect in a billiard impact experiment in two thirds of the cases. In all other instances, the electron is seemingly reflected by the nucleus and sometimes even ejected in the opposite direction.

Reinhard Dörner: “This allowed us to show that the entire system of photon, ejected electron and ion oscillate according to quantum mechanical laws. Our experiments therefore provide a new approach for experimental testing of quantum mechanical theories of Compton scattering, which plays an important role, particularly in astrophysics and X-ray physics.”

Publication: Kinematically complete experimental study of Compton scattering at helium atoms near the ionization threshold. Max Kircher (Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany (GU)), Florian Trinter (Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY, Hamburg, Germany, and Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin), Sven Grundmann (GU), Isabel Vela-Perez (GU), Simon Brennecke (Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany), Nicolas Eicke (Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany), Jonas Rist (GU), Sebastian Eckart (GU), Salim Houamer (University Sétif-1, Algeria), Ochbadrakh Chuluunbaatar (Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, Russia (JINR); National University of Mongolia, Ulan-Bator), Yuri V. Popov (Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia; JINR), Igor P. Volobuev (Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia), Kai Bagschik (DESY) M. Novella Piancastelli (Sorbonne Universités, Paris, France; Uppsala University, Sweden) Manfred Lein (Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany), Till Jahnke (GU), Markus S. Schöer (GU), Reinhard Dörner (GU)

Nature Physics, DOI 10.1038/s41567-020-0880-2; https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-020-0880-2

Pictures may be downloaded here: http://www.uni-frankfurt.de/87402622

Caption Graphics: Artist view of the process and cross section for Compton scattering (front) and the COLTRIMS reaction microscope which enabled the experiment (back). Photons (wiggly line) hit an electron in the atom in the centre of the COLTRIMS reaction microscope knocking out an electron (red ball) and leaving an ion (blue ball) behind. Both particles are guided by electric and magnetic fields toward detectors (red and blue discs.) Copyright: Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

Caption Photo: Selfie of Max Kircher in front of the COLTRIMS reaction microscope.

Further information:

Professor Reinhard Dörner

Institute for Atomic Physics

Goethe University Frankfurt

Max-von-Laue-Strasse 1

60438 Frankfurt

Telephone +49 69 798 47003

doerner@atom.uni-frankfurt.de

http://www.atom.uni-frankfurt.de

Current news about science, teaching, and society can be found on GOETHE-UNI online (www.aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de)

Goethe University is a research-oriented university in the European financial centre Frankfurt am Main. The university was founded in 1914 through private funding, primarily from Jewish sponsors, and has since produced pioneering achievements in the areas of social sciences, sociology and economics, medicine, quantum physics, brain research, and labour law. It gained a unique level of autonomy on 1 January 2008 by returning to its historic roots as a “foundation university”. Today, it is one of the three largest universities in Germany. Together with the Technical University of Darmstadt and the University of Mainz, it is a partner in the inter-state strategic Rhine-Main University Alliance. Internet: www.uni-frankfurt.de

Publisher: The President of Goethe University Editor: Dr. Markus Bernards, Science Editor, PR & Communication Department, Theodor-W.-Adorno-Platz 1, 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Tel: -49 (0) 69 798-12498, Fax: +49 (0) 69 798-763 12531, bernards@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

Professor Reinhard Dörner

Institute for Atomic Physics

Goethe University Frankfurt

Max-von-Laue-Strasse 1

60438 Frankfurt

Telephone +49 69 798 47003

doerner@atom.uni-frankfurt.de

http://www.atom.uni-frankfurt.de

Kinematically complete experimental study of Compton scattering at helium atoms near the ionization threshold. Max Kircher et. al. Nature Physics, DOI 10.1038/s41567-020-0880-2; https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-020-0880-2

https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/englisch/physics-frankfurt-researchers-solve-…

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…