Magnetic fields set the stage for the birth of new stars

Image of the Triangulum Galaxy M33, which presents astronomers with a bird’s eye view of its disk. The pink blobs are regions containing newly formed stars.<br>Credit & Copyright: Thomas V. Davis (http://tvdavisastropics.com)<br>

Their results suggest that such magnetic fields play a key role in channeling matter to form denser clouds, and thus in setting the stage for the birth of new stars. The work will be published in the November 24 edition of the journal Nature (online version: November 16).

Stars and their planets are born when giant clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse. You've probably seen the resulting stellar nurseries in beautiful astronomical images: Colorful nebulae, lit by the bright young stars they have brought forth.

Astronomers know quite a bit about these so-called molecular clouds: They consist mainly of hydrogen molecules – unusual in a cosmos where conditions are rarely right for hydrogen atoms to bond together into molecules. And if one traces the distribution of clouds in a spiral galaxy like our own Milky Way galaxy, one finds that they are lined up along the spiral arms.

But how do those clouds come into being? What makes matter congregate in regions a hundred or even a thousand times more dense than the surrounding interstellar gas?

One candidate mechanism involves the galaxy's magnetic fields. Everyone who has seen a magnet act on iron filings in the classic classroom experiment knows that magnetic fields can be used to impose order. Some researchers have argued that something similar goes on in the case of molecular clouds: that galaxies' magnetic fields guide and direct the condensation of interstellar matter to form denser clouds and facilitate their further collapse.

Some astronomer see this as the key mechanism enabling star formation. Others contend that the cloud matter's gravitational attraction and turbulent motion of gas within the cloud are so strong as to cancel any influence of an outside magnetic field.

If we were to restrict attention to our own galaxy, it would be difficult to find out who is right. We would need to see our galaxy's disk from above to make the appropriate measurements; in reality, our Solar System sits within the galactic disk. That is why Hua-bai Li and Thomas Henning from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy chose a different target: the Triangulum galaxy, 3 million light-years from Earth and also known as M 33, which is oriented in just the right way (cf. image).

Using a telescope known as the Submillimeter Array (SMA), which is located at Mauna Kea Observatory on Mauna Kea Island, Hawai'i, Li and Henning measured specific properties of radiation received from different regions of the galaxy which are correlated with the orientation of these region's magnetic fields. They found that the magnetic fields associated with the galaxy's six most massive giant molecular clouds were orderly, and well aligned with the galaxy's spiral arms.

If turbulence played a more important role in these clouds than the ordering influence of the galaxy's magnetic field, the magnetic field associated with the cloud would be random and disordered.

Thus, Li and Henning's observations are a strong indication that magnetic fields indeed play an important role when it comes to the formation of dense molecular clouds – and to setting the stage for the birth of stars and planetary systems like our own.

Contact information

Hua-bai Li (first author)

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg

Phone: (+49|0) 6221 – 528 459

Email: li@mpia.de

Thomas Henning (co-author)

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg

Phone: (+49|0) 6221 – 528 200

Email: henning@mpia.de

Markus Pössel (public relations)

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

Phone: (+49|0) 6221 – 528 261

Email: pr@mpia.de

Background information

The work described here will be published in the November 24, 2011 edition of Nature as H. Li and T. Henning, “The alignment of molecular cloud magnetic fields with the spiral arms in M33”. The article will be published online on November 16.

The research is supported by the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The Submillimeter Array is a joint project between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics and is funded by the Smithsonian Institution and the Academia Sinica.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

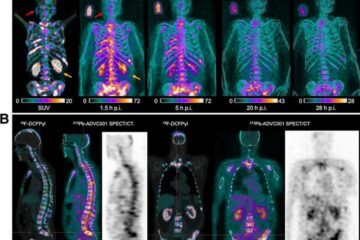

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…