Black Hole Growth Found to be Out of Synch

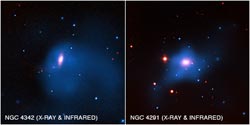

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/A.Bogdan et al; Infrared: 2MASS/UMass/IPAC-Caltech/NASA/NSF<br>

Astronomers long have thought that a supermassive black hole and the bulge of stars at the center of its host galaxy grow at the same rate — the bigger the bulge, the bigger the black hole. A new study of Chandra data has revealed two nearby galaxies whose supermassive black holes are growing faster than the galaxies themselves.

The mass of a giant black hole at the center of a galaxy typically is a tiny fraction (about 0.2 percent) of the mass contained in the bulge, or region of densely packed stars, surrounding it. The targets of the latest Chandra study, galaxies NGC 4342 and NGC 4291, have black holes that are 10 times to 35 times more massive than they should be compared to their bulges. The new observations with Chandra show that the halos, or massive envelopes of dark matter in which these galaxies reside, also are overweight.

The new study suggests the two supermassive black holes and their evolution are tied to their dark matter halos and they did not grow in tandem with the galactic bulges. In this view, the black holes and dark matter halos are not overweight, but the total mass in the galaxies is too low.

“This gives us more evidence of a link between two of the most mysterious and darkest phenomena in astrophysics — black holes and dark matter — in these galaxies,” said Akos Bogdan of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Mass, who led the new study.

NGC 4342 and NGC 4291 are close to Earth in cosmic terms, at distances of 75 million and 85 million light years, respectively. Astronomers had known from previous observations that these galaxies host black holes with relatively large masses, but astronomers are not certain what is responsible for the disparity. Based on the new Chandra observations, however, they are able to rule out a phenomenon known as tidal stripping.

Tidal stripping occurs when some of a galaxy's stars are stripped away by gravity during a close encounter with another galaxy. If such tidal stripping had taken place, the halos also mostly would have been missing. Because dark matter extends farther away from the galaxies, it is more loosely tied to them than the stars and is more likely to be pulled away.

To rule out tidal stripping, astronomers used Chandra to look for evidence of hot, X-ray emitting gas around the two galaxies. Because the pressure of hot gas – estimated from X-ray images — balances the gravitational pull of all the matter in the galaxy, the new Chandra data can provide information about the dark matter halos. The hot gas was found to be widely distributed around both NGC 4342 and NGC 4291, implying that each galaxy has an unusually massive dark matter halo, and therefore that that tidal stripping is unlikely.

“This is the clearest evidence we have, in the nearby universe, for black holes growing faster than their host galaxy,” said co-author Bill Forman, also of CfA. “It's not that the galaxies have been compromised by close encounters, but instead they had some sort of arrested development.”

How can the mass of a black hole grow faster than the stellar mass of its host galaxy? The study's authors suggest that a large concentration of gas spinning slowly in the galactic center is what the black hole consumes very early in its history. It grows quickly, and as it grows, the amount of gas it can accrete, or swallow, increases along with the energy output from the accretion. Once the black hole reaches a critical mass, outbursts powered by the continued consumption of gas prevent cooling and limits the production of new stars.

“It's possible that the supermassive black hole reached a hefty size before there were many stars at all in the galaxy,” said Bogdan. “That is a significant change in our way of thinking about how galaxies and black holes evolve together.”

These results were presented June 11 at the 220th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Anchorage, Alaska. The study also has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., manages the Chandra program for the agency's NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Mass., controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

For Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/chandra

For an additional interactive image, podcast, and video on the finding, visit:

http://chandra.si.edu

Media contacts:

J.D. Harrington

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-0321

j.d.harrington@nasa.gov

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Mass.

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.cfa.harvard.eduAll latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

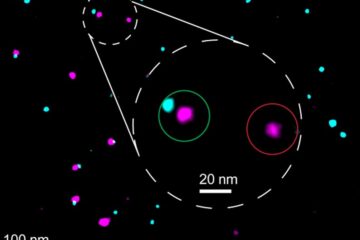

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…