Astronomers hazard a ride in a 'drifting carousel' to understand pulsating stars

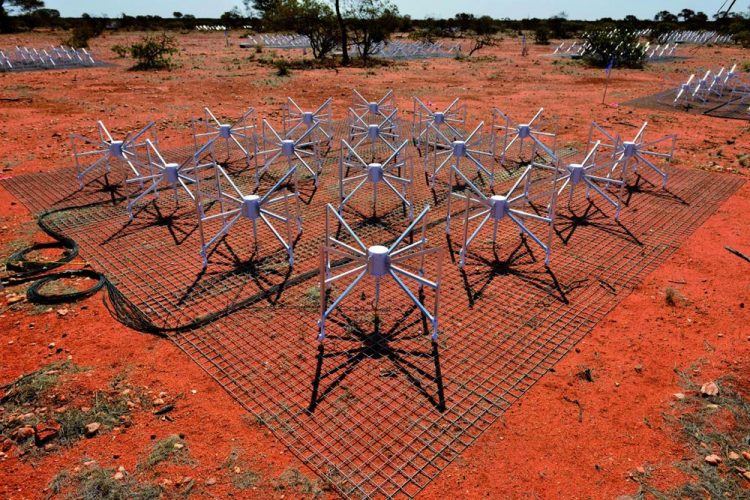

Antenna 'tiles' of the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) are in the Western Australian desert. Image credit: MWA Project / Curtin University

New research from Curtin University, obtained using the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) radio telescope located in the Western Australian outback, suggests the answer could lie in a 'drifting carousel' found in a special class of pulsars.

Curtin PhD student Sam McSweeney, who led the research as part of his PhD project with the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO) and the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), described pulsars as extremely dense neutron stars that emit beams of radio waves.

“These pulsars weigh about half a million times the mass of the Earth but are only 20km across,” Mr McSweeney said.

“They are nicknamed 'lighthouses in space' because they appear to 'pulse' once per rotation period, and their sweeping light signal can be seen through telescopes at exceptionally regular intervals.”

Thousands of pulsars have been seen since their first discovery in the late 1960s, but questions still remain as to why these stars emit radio beams in the first place, and what type of emission model best describes the radio waves, or 'light', that we see.

“The classical pulsar model pictures the emission that is shooting out from the magnetic poles of the pulsar as a light cone,” Mr McSweeney said.

“But the signal that we observe with our telescopes suggests a much more complex structure behind this emission – probably coming from several emission regions, not just one.”

The 'drifting carousel' model manages to explain this complexity much better, describing the emission as coming from patches of charged particles, arranged in a rotating ring around magnetic field lines, or a carousel.

“As each patch releases radiation, the rotation generates a small drift in the observed signal of these sub-pulses that we can detect using the MWA,” Mr McSweeney said.

“Occasionally, we find that this sub-pulse carousel gets faster and then slower again, which can be our best window into the plasma physics underlying the pulsar emission.”

One possibility the researchers are currently testing is that surface temperature is responsible for the carousel changing rotation speed: localised 'hotspots' on the pulsar surface might cause it to speed up.

“We will observe individual pulses from these drifting pulsars across a wide range of radio frequencies, with lower frequency data than ever before,” Mr McSweeney said.

“Looking at the same pulsar with different telescopes simultaneously will allow us to trace the emission at different heights above their surface.”

The researchers plan to combine the data from the MWA, the Giant Metre-wave Radio Telescope in India and the CSIRO Parkes Radio Telescope in New South Wales to – literally – get to the bottom of the mysterious pulses.

###

A paper explaining the research, Low Frequency Observations of the Subpulse Drifter PSR J0034-0721 with the Murchison Widefield Array, was recently published in The Astrophysical Journal. An explanatory video is available under: https:/

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…