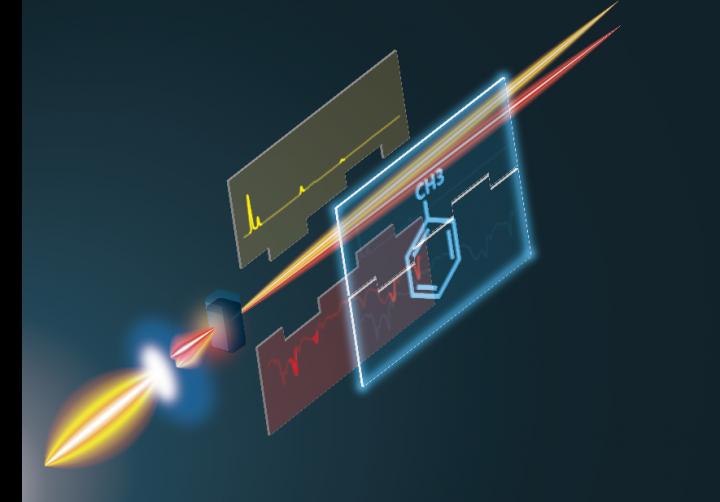

A laser, a crystal and molecular structures

The new technique of complementary vibrational spectroscopy relies on improvements in ultrashort pulsed laser technology. Researchers at the University of Tokyo hope to use complementary vibrational spectroscopy to see molecules change shape in real time without invasive techniques. Image by Takuro Ideguchi, CC BY-ND-4.0 Usage Restrictions: Please cite the image credit when publishing. This material may be freely used by reporters as part of news coverage, with proper attribution.

Researchers have built a new tool to study molecules using a laser, a crystal and light detectors. This new technology will reveal nature's smallest sculptures – the structures of molecules – with increased detail and specificity.

“We live in the molecular world where most things around us are made of molecules: air, foods, drinks, clothes, cells and more. Studying molecules with our new technique could be used in medicine, pharmacy, chemistry, or other fields,” said Associate Professor Takuro Ideguchi from the University of Tokyo Institute for Photon Science and Technology.

The new technique combines two current technologies into a unique system called complementary vibrational spectroscopy. All molecules have very small, distinctive vibrations caused by the movement of the atoms' nuclei. Tools called spectrometers detect how those vibrations cause molecules to absorb or scatter light waves. Current spectroscopy techniques are limited by the type of light that they can measure.

The new complementary vibrational spectrometer designed by researchers in Japan can measure a wider spectrum of light, combining the more limited spectra of two other tools, called infrared absorption and Raman scattering spectrometers. Combining the two spectroscopy techniques gives researchers different and complementary information about molecular vibrations.

“We questioned the 'common sense' of this field and developed something new. Raman and infrared spectra can now be measured simultaneously,” said Ideguchi.

Previous spectrometers could only detect light waves with lengths from 0.4 to 1 micrometer (Raman spectroscopy) or from 2.5 to 25 micrometers (infrared spectroscopy). The gap between them meant that Raman and infrared spectroscopy had to be performed separately. The limitation is like trying to enjoy a duet, but being forced to listen to the two parts separately.

Complementary vibrational spectroscopy can detect light waves around the visible to near-infrared and mid-infrared spectra. Advancements in ultrashort pulsed laser technology have made complementary vibrational spectroscopy possible.

Inside the complementary vibrational spectrometer, a titanium-sapphire laser sends pulses of near-infrared light with the width of 10 femtoseconds (10 quadrillionths of a second) towards the chemical sample. Before hitting the sample, the light is focused onto a crystal of gallium selenide. The crystal generates mid-infrared light pulses. The near- and mid-infrared light pulses are then focused onto the sample, and the absorbed and scattered light waves are detected by photodetectors and converted simultaneously into Raman and infrared spectra.

So far, researchers have tested their new technique on samples of pure chemicals commonly found in science labs. They hope that the technique will one day be used to understand how molecules change shape in real time.

“Especially for biology, we use the term 'label-free' for molecular vibrational spectroscopy because it is noninvasive and we can identify molecules without attaching artificial fluorescent tags. We believe that complementary vibrational spectroscopy can be a unique and useful technique for molecular measurements,” said Ideguchi.

###

Research Paper

Hashimoto K., Badarla V.R., Kawai A., and Ideguchi T. (27 September 2019). Complementary Vibrational Spectroscopy. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-12442-9 http://dx.

Related Links

Ideguchi Laboratory: https:/

Department of Biological Sciences: http://www.

Graduate School of Science: https:/

Twitter: @IdeguchiTakuro

Research contact

Associate Professor Takuro Ideguchi

Institute for Photon Science and Technology, The University of Tokyo

Tel: +81-(0)3-5841-1026

Email: ideguchi@gono.phys.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Press Contact

Ms. Caitlin Devor

Division for Strategic Public Relations, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, JAPAN

Tel: +81-(0)3-5841-0876

Email: press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at http://www.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…