There's a better way to decipher DNA's epigenetic code to identify disease

Enzymes, rather than harsh chemical reactions, can be used to reveal the epigenetic code in DNA. Credit: Rahul Kohli, Univeristy of Pennsylvania

A new method for sequencing the chemical groups attached to the surface of DNA is paving the way for better detection of cancer and other diseases in the blood, according to research from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania published today in Nature Biotechnology. These chemical groups mark one of the four DNA “letters” in the genome, and it is differences in these marks along DNA that control which genes are expressed or silenced.

To detect disease earlier and with increased precision, researchers have a growing interest in analyzing free-floating DNA in settings in which there is a limited amount, such as that extruded from tumors into the bloodstream.

“We're hopeful that this method offers the ability to decode epigenetic marks on DNA from small and transient populations of cells that have previously been difficult to study, in order to determine whether the DNA is coming from a specific tissue or even a tumor.” said co-senior author Rahul Kohli, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics, and Medicine.

Researchers from Penn and elsewhere have investigated these DNA modifications over the last two decades to better understand and diagnose an array of disorders, most notably cancer. For the last several decades, the major methods used to decipher the epigenetic code have relied on a chemical called bisulfite. While bisulfite has proven useful, it also presents major limitations: it is unable to differentiate the most common modifications on the DNA building block cytosine, and more significantly, it destroys much of the DNA it touches, leaving little material to sequence in the lab.

The new method described in this paper builds on the fact that a class of immune-defense enzymes, called APOBEC DNA deaminases, can be repurposed for biotech applications. Specifically, the deaminase-guided chemical reaction is able to achieve what bisulfite could do, but without harming DNA.

“This technological advance paves the way to better understand complex biological processes such as how the nervous system develops or how a tumor progresses,” said co-senior author Hao Wu, PhD, an assistant professor of Genetics. Kohli's graduate student Emily Schutsky is first author on the study.

Using this method, the team showed that determining the epigenetic code of one type of neuron used 1,000-times less DNA than required by the bisulfite-dependent methods. From this, the new method could also differentiate between the two most common epigenetic marks, methylation and hydroxmethylation.

“We were able to show that sites along the genome that appear to be modified are in fact very different in terms of the distribution of these two marks,” Kohli said. “This finding suggests important and distinctive biological roles for the two marks on the genome.”

###

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21-HG009545, R00-HG007982, DP2-HL142044, R01-GM118501, T32-GM07229, F30-CA196097).

Editor's note: Aspects of the ACE-Seq protocol have been non-exclusively licensed to Penn. The authors have no conflicts to disclose regarding this licensing.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $7.8 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top medical schools in the United States for more than 20 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $405 million awarded in the 2017 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center — which are recognized as one of the nation's top “Honor Roll” hospitals by U.S. News & World Report — Chester County Hospital; Lancaster General Health; Penn Medicine Princeton Health; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital – the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine, and Princeton House Behavioral Health, a leading provider of highly skilled and compassionate behavioral healthcare.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2017, Penn Medicine provided $500 million to benefit our community.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

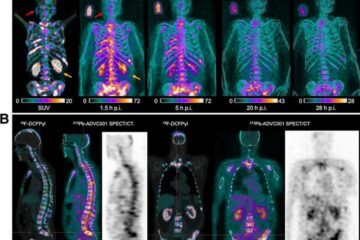

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…