Secrets Of Successful Pathogen Revealed

Two groups of scientists have uncovered key secrets of success of a major pathogen responsible for recent food poisoning outbreaks. The ability of Salmonella bacteria to act quickly, both on an evolutionary timescale and during the early minutes of infection, has been investigated in detail for the first time.

This month more than 1,700 cases of Salmonella food poisoning from chicken were reported in Spain and earlier outbreaks in Europe have been linked to lettuce and eggs.

“For bacteria to do well, they have to react very fast, and we have shown Salmonella to be remarkably dynamic”, says Professor Jay Hinton of the UK’s Institute of Food Research (IFR).

In a study published tomorrow by IFR and Sweden’s Uppsala University, scientists found that Salmonella can evolve at a surprisingly rapid rate by jettisoning superfluous DNA.

One hundred million years ago Salmonella evolved from E. coli bacteria that lived freely in the environment. Salmonella developed the ability to parasitize animals by losing many genes and gaining new ones from other bacteria.

Using DNA microarrays to analyse the results of “experimental evolution”, the scientists tracked Salmonella in real time over 6,750 generations to make the first estimation of the rate of gene loss for any bacterium.

Project leader Professor Dan Andersson says: “Nearly one quarter of the bacteria’s genes could be lost in only 50,000 years. This was a surprise to us as it had been thought this process would take many millions of years”.

In separate research, Professor Hinton of IFR and Professor John Ladbury of UCL (University College London) investigated the response of Salmonella to body temperature. This had not been studied before.

“Bacteria are efficient organisms”, says Professor Hinton. “We found that at low temperatures Salmonella switches off genes required for infection and switches them on once inside a warm animal body. It does not want to expend energy needlessly when waiting to be eaten on a lettuce leaf”.

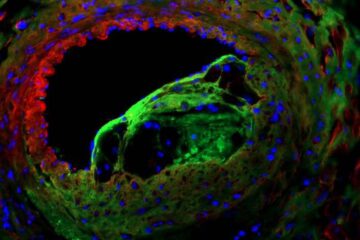

The team discovered the thermal switch, a protein called H-NS, and found that it allows 532 genes to be activated within minutes. These genes code for functions essential for infection such as the ability to swim and to infect gut cells.

Professor Ladbury believes that as the temperature rises, the protein structure which compacts Salmonella DNA changes shape, allowing gene expression to start.

“These findings help to explain the success of this pathogen in infecting so many different species of animals and reptiles, as well as man”, says Professor Hinton.

Salmonella kills about 1 million people worldwide every year, and now kills more people in the West than any other foodborne pathogen.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ifr.ac.ukAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…

Mini-colons revolutionize colorectal cancer research

As our battle against cancer rages on, the quest for more sophisticated and realistic models to study tumor development has never been more critical. Until now, research has relied on…