New method of turning off viruses may help control HIV infection, says Jefferson scientist

A natural method of disarming some types of viruses may enable scientists to someday treat infections with HIV, the AIDS virus, according to a virologist at Jefferson Medical College.

Taking the lead from the common fruit fly, yeast and worms, scientists have recently shown that it may be possible to use small pieces of genetic material called short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to inhibit HIV from making more copies of itself.

The process, called RNA interference (RNAi), was first discovered in 1998. It is so novel, says virologist Roger J. Pomerantz, M.D., professor of medicine, biochemistry and molecular pharmacology and chief of the division of infectious diseases at Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, that scientists only now are beginning to understand its potential to treat disease. “What’s so exciting for HIV therapy is that it may be a potent way of specifically inhibiting the virus,” says Dr. Pomerantz, whose commentary accompanies a paper on the topic in the July 2002 issue of Nature Medicine.

“Does it [RNAi] work in mammals? That would be the Holy Grail,” says Dr. Pomerantz, who is also director of the Center for Human Virology at Jefferson Medical College. “Researchers are showing it in mouse cells and now a team has demonstrated it in human cells.”

So-called “gene silencing” isn’t new. According to Dr. Pomerantz, scientists have known for several decades that organisms can and do shut off the expression of certain genes. But, he says, no one until recently has been able to show this was occurring during the gene replication process. Scientists showed that they could stop a gene from replicating by degrading the gene’s RNA and making its protein product.

Researchers learned several years ago that certain organisms – some worms, fruit flies, yeast and even plants – use a type of RNA called double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to shut off genes. Dr. Pomerantz explains that dsRNA is cut up by an enzyme, “Dicer,” into smaller siRNAs, which in turn attach to RNA being made by the cell, rendering it useless.

Scientists showed recently that RNAi could work in mammalian cells. In the current issue of Nature Medicine, researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology reported a series of experiments demonstrating how siRNAs might be used to fight HIV, which is an RNA virus. They used siRNAs in two ways. They showed they could silence both cellular genes necessary for HIV infection and also use siRNAs to quiet an HIV gene itself.

Dr. Pomerantz points out that the MIT report is an important step in understanding the process. “This [MIT work] is a proof of concept,” he says. “The MIT team showed RNAi could work for HIV.

“Now, we need to figure out how it works and how long it lasts,” he says. “Does it spread between cells? How robust is it in inhibiting HIV? Can we use it against virtually any RNA virus?” RNAi may also be useful against cancer-causing oncogenes, he adds.

“I think it [this technology] is going to explode,” Dr. Pomerantz says. “It has the potential to lead to novel forms of drugs for many diseases, but there’s a lot of science to be done first to catch up to these observations.”

Contact: Steve Benowitz or Phyllis Fisher, 215-955-6300. After Hours: 215-955-6060

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

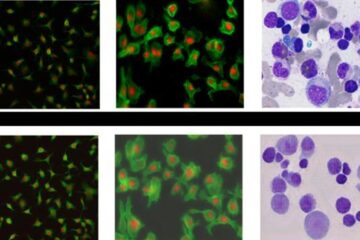

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…