Gene mutation leads to poorly understood birth defects

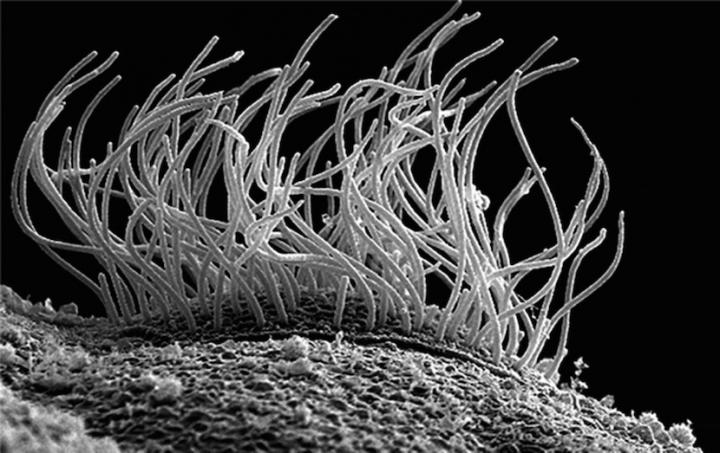

Cilia Credit: John Wallingford

Birth defects from genetic disorders of the cilia — tentacle-like structures in cells that coordinate cell-to-cell communication in healthy people — are varied, ranging from oral-facial-digital syndrome, which can cause extra toes, misshapen teeth, an abnormal tongue and other defects, to short rib polydactyly syndrome, a lethal birth defect that causes every organ in the body to be defective.

“For cells to talk to each other, functioning cilia are needed,” says Wallingford, a professor in the Department of Molecular Biosciences. “We identified a group of proteins that form part of the base that cilia need in order to function. If that base is defective, it can cause serious birth defects that are frequently lethal.”

The new research pinpoints how three proteins work together to form a base that allows cilia to carry critical cell-to-cell communications. Wallingford and his colleagues discovered that, much the way that cellphone towers provide a base for the antennas that assist with communication, these proteins together construct a base that anchors the cilia.

Disturbances in the little-known group of proteins, which the researchers called CPLANE, led to disturbed cell communication and observable ciliopathy in mouse models. The team also asked human geneticists to screen for the genes among their patients with similar birth defects and found that mutations in the same genes resulted in ciliopathies in humans.

Wallingford points out that the research is important, given that ciliopathies are more widespread than most people realize. Polycystic kidney disease, for example, which causes the abnormal growth of cysts on kidneys, is a disorder arising from defective cilia and afflicts about 600,000 people in the U.S.

“If you lump ciliopathies, the prevalence is high, and they will become one of the more common congenital diseases,” says Wallingford. “Birth defects are an underappreciated problem, and we have little understanding of their genetic underpinnings despite their prevalence, not to mention their environmental underpinnings.”

###

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Co-authors of the paper are from the University of California, Los Angeles; FHU TRANSLAD, Burgundy University, France; Stanford University School of Medicine; Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School; University Hospital Center, Liège, Belgium; Hospital Center, Luxembourg; Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Belgium; Pediatric Centre PGIMER, Chandigarh, India; Federico II University of Naples, Italy; Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine, Naples, Italy; Dental Institute, King's College London, U.K.; Stony Brook University, New York; Mendelian Center, University of Washington; and Children Hospital, Dijon, France.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…