Trapped in a ring – Ring-like protein complex helps ensure accurate protein production

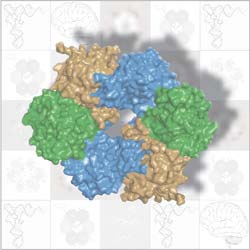

The ring-like part of Elongator that holds tRNA in place is formed by three proteins (brown, green, blue) paired up in two trios. ©EMBL/S.Glatt <br>

In fairy tales, magic rings endow their owners with special abilities: the ring makes the wearer invisible, fulfils his wishes, or otherwise helps the hero on the path to his destiny.

Similarly, a ring-like structure found in a protein complex called ‘Elongator’ has led researchers at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, and the Institut de Génétique et Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire (IGBMC) in Strasbourg, France, in exciting new directions. Published today in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, the first three-dimensional structure of part of this complex provides new clues to its tasks inside the cell and to its role in neurodegenerative diseases.

Changes to the proteins that make up Elongator have been linked to disorders such as familial dysautonomia and childhood epilepsy, and scientists knew that the complex is involved in a variety of processes inside the cell, but exactly what it does has so far remained a mystery.

Elongator is composed of 6 different proteins. Scientists in Christoph Müller’s lab at EMBL and Bertrand Séraphin’s lab at IGBMC looked at three of these proteins, which are known to work together. They discovered that, instead of just clumping together as a trio, these proteins team up in two identical trios to form a ring. This unexpected structure sparked new thoughts. It suggested that the ring’s job in the Elongator complex might be similar to that of other protein complexes, called helicases, which use ring-like structures made out of six copies of the same protein to bind to DNA or RNA.

The researchers found only one molecule that slots into Elongator’s ring: tRNA. tRNA transports amino acids to the ‘factories’ in the cell where they will be stitched together into a protein according to the instructions spelled out in the cell’s DNA. It seems that Elongator’s protein ring holds the tRNA in place while other parts of the Elongator complex work on it, introducing a chemical modification which ultimately ensures that the DNA is accurately converted into protein. The findings also suggest that, once work on the tRNA is complete, a different molecule, ATP, is broken down on the outer margin of the ring. This, the scientists believe, would subtly alter the shape of the ring’s proteins, releasing the tRNA and allowing the whole process to start again.

Next, Müller, Séraphin and colleagues would like to investigate what tools and tricks other parts of Elongator employ to help the whole complex perform its tasks inside the cell.

Published online in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology on 19 February 2012. DOI: 10.1038/nsmb.2234

Deutsch Kontakt:

Angela Michel

Meyerhofstr. 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Deutschland

Tel.: +49 (0)6221 387 8443

Fax: +49 (0)6221 387 8525

michel@embl.de

Sonia Furtado Neves

EMBL Press Officer

Meyerhofstr. 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)6221 387 8263

Fax: +49 (0)6221 387 8525

sonia.furtado@embl.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.embl.orgAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…