The mutations that matter

Scheme of the four determinant structural differences between enzymatically active and inactive glutaredoxins TU Kaiserslautern, M. Deponte

Four mutations in a group of proteins, called glutaredoxins, determine how the proteins operate in everything from bacteria and yeast to plants and humans, researchers report in the journal Nature Communications.

“These proteins are central to essential metabolic pathways,” said Professor Marcel Deponte, a biochemist who led the research at the Technische Universität Kaiserslautern. “Learning more about them improves our basic understanding of how life works.”

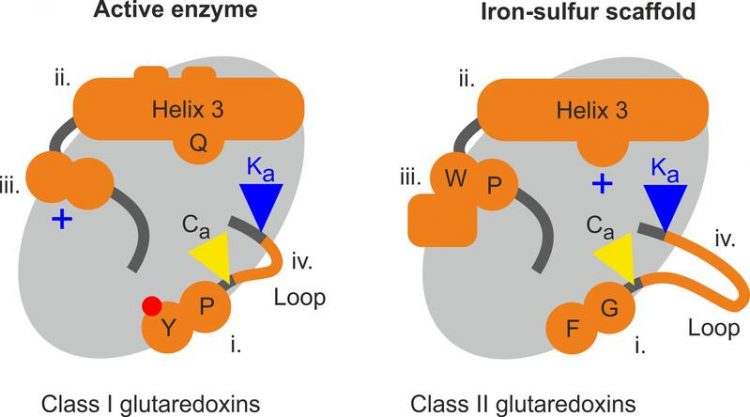

There are two major classes of glutaredoxin proteins. Class I glutaredoxins are enzymes that catalyze important redox reactions, such as the synthesis of the precursors of DNA. Class II glutaredoxins are not active catalysts, but rather help sense and transport iron-sulfur clusters, a key part of iron metabolism.

While biochemists have known about the two types for well over 20 years, it was unclear what structural differences are responsible for the distinct functions. Deponte teamed up with researchers at the Universität des Saarlandes and Heinrich-Heine-Universität in Düsseldorf to investigate the proteins in test tubes, in yeast cells and in computational models.

Nuclear magnetic resonance structures revealed four areas containing differences, or mutations, between the Class I and Class II amino acid sequences. Deponte and his collaborators wanted to know exactly how much each mutation contributed to making the protein a catalytically active Class I or an inactive Class II glutaredoxin.

To measure this, they used a combination of editing and tracking techniques. First, they produced and purified the proteins in order to analyze their activity in a test tube assay. Normally, an active Class I enzyme would catalyze, or assist, a redox reaction, which are chemical reactions involving the transfer of electrons between molecules.

The team systematically replaced regions in the inactive Class II protein with corresponding regions from the active Class I proteins, and vice versa. The most notable physical difference between the two classes is a long loop present in the inactive Class II proteins. When the researchers cut out the long loop and replaced it with the shorter one from a Class I protein, they observed slightly increased catalytic activity.

However, in combination with other mutations, the activity of the Class II protein progressively increased. The researchers concluded that the long loop acts like an off switch in the inactive Class II, and that introduction of all four mutations from Class I glutaredoxins was required to fully convert the inactive protein into an active one.

Ultimately, they were able to turn inactive proteins, whose job is normally to sense or deliver iron-sulfur clusters, into active enzymes catalyzing redox reactions; and vice versa.

“Mutations in all four areas work together to make the protein either an active redox catalyst or an iron-binding protein,” Deponte said.

The Saarlandes biochemistry team, led by Professor Bruce Morgan, then developed an assay to test the relevance of the mutations in live yeast cells, confirming the same pattern of results – all four mutations are required for complete transition between the two classes.

For these analyses, the researchers used a green fluorescent probe that changes its fluorescence when it senses redox reactions. The altered light from the fluorescent probe signaled how much a mutation enabled the protein to catalyze redox reactions in the cells.

Meanwhile, the Düsseldorf Computational Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Molecular Bioinformatics Group, led by Professor Holger Gohlke, ran molecular dynamics simulations using supercomputers, which also supported and complemented the findings.

Taken together, the three lines of inquiry “provide a really convincing picture that we understand how these proteins work,” Deponte said. The finding was made possible through a priority program grant encouraging this type of collaboration by the German Research Foundation, he added.

Next steps could include exploring the effects these mutations have on human cells or applying a similar investigatory process to other proteins. Thanks to advances in genetic sequencing technologies, thousands of proteins have been decoded, but scientists have barely scratched the surface of understanding what they do or how they function.

Original Publication:

M. Deponte et al., “Quantitative assessment of the determinant structural differences between redox-active and inactive glutaredoxins”, Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-15441-3 (04/2020)

Image Caption:

Image 1: “Scheme of the four determinant structural differences between enzymatically active and inactive glutaredoxins”

Image 2:

“Comparison of the four determinant structural differences between enzymatically active and inactive glutaredoxins”

Image Rights: TU Kaiserslautern, M. Deponte

For further questions please contact:

Prof. Dr. Marcel Deponte

TU Kaiserslautern

Tel: 0631 – 205 4060

deponte@chemie.uni-kl.de

Wissenschaftliche Ansprechpartner:

Prof. Dr. Marcel Deponte

TU Kaiserslautern

Tel: 0631 – 205 4060

deponte@chemie.uni-kl.de

M. Deponte et al., “Quantitative assessment of the determinant structural differences between redox-active and inactive glutaredoxins”, Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-15441-3 (04/2020)

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-kl.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…