Researchers from Dresden discover protein for more mobility

Prof. Martina Rauner und Dr. Ulrike Baschant (v.l.n.r.) Foto: Medizinische Fakultät Carl Gustav Carus der TU Dresden / Stephan Wiegand

A total of four million children and adults in Germany are affected by one of more than 6,000 rare diseases. Many of these diseases are still rather unexplored, and there is still no effective therapy for the majority of these diseases.

Take Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP). For patients, the diagnosis means the progressive ossification of soft tissue and muscles.

Healthy muscles, ligaments and tendons transform into bones – all in the wrong place – resulting in stiffness and permanent immobility as if you were permanently trapped in a cast.

The growth of bone-like structures where usually no bone is (ectopic ossification) may occur without warning or is triggered by a slight bump. The underlying cause is a gene defect that leads to a defective building plan for the ACVR1 receptor.

Scientists of the Bone Lab of the University Hospital at the TU Dresden have now discovered a protein that links two apparently unrelated systems.

Transferrin receptor-2 (Tfr2), responsible for iron metabolism, was discovered as a new component in bone metabolism. Tfr2 binds to so-called bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), which are responsible for the mineralization of bone.

Together with an interdisciplinary team of international researchers, the Bone Lab has now discovered that the binding region of Tfr2 can also be used to neutralize BMPs to prevent misplaced bone formation. Professor Martina Rauner and her colleagues were surprised:

“When we saw how potent the binding region of Tfr2 inhibited the undesired soft tissue ossification in the animal model, we realized that this discovery may have the potential for clinical development.”

Martina Rauner, biotechnologist and scientific director of the “Bone Lab” has dedicated her career to the study of bone diseases. It took years of intensive collaboration to decipher the therapeutic potential.

So far, there is no suitable therapy for the approximately 700 patients worldwide and the 30 people affected by FOP in Germany. However, now there is new hope, states Dr Ulrike Baschant: “Kymab, a therapeutic anti-body company in Cambridge, will promote the clinical development of Tfr2 based on our discovery in Dresden.”

This landmark discovery is significant not only for patients with FOP, but also for those with more common skeletal disorders, such as heterotopic ossification, a disease that occurs after hip replacement surgery or major trauma.

The two main authors, Martina Rauner and Ulrike Baschant, report about their finding in the journal Nature Metabolism. The discovery of the protein was the result of international cooperation for many years, amongst others with scientists from the University of Torino in Italy.

With the help of a dozen scientists, they worked in the lab to solve another puzzle of science. Martina Rauner is happy that the “newly created knowledge may serve novel therapies that could improve the lives of children and adults with bone diseases”. Ulrike Baschant adds, “It is a decisive step towards regaining physical independence and personal freedom!”

Prof. Dr. Martina Rauner

Scientific Director “Bone Lab”

Medical Clinic III

University Centre for Healthy Ageing

University Hospital and Medical Faculty Carl Gustav Carus of TU Dresden

Phone: +49 351 458 4206

E-Mail: Martina.Rauner@ukdd.de

Transferrin receptor 2 controls bone mass and pathological bone formation via BMP and Wnt signalling, in: Nature Metabolismvolume 1, pages111–124 (2019) , doi.org/10.1038/s42255-018-0005-8, https://www.nature.com/articles/s42255-018-0005-8

https://www.sfb655.de/START/projekte/bereich-b/b13-hofbauer-platzbecker

https://www.kymab.com/

https://www.bone-lab.de/

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

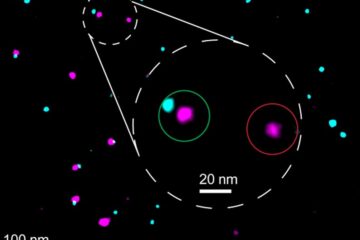

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…