Titanium dioxide — It slices, it dices …

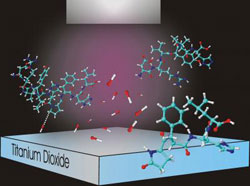

Illustration of the cleavage of proteins near a titanium dioxide surface: when illuminated with ultraviolet light, hydroxyl radicals are formed in water near the semiconductor's surface and cut proteins at the location of the amino acid proline. Credit: NIST

Because most proteins are very large, complex molecules made up of hundreds or thousands of amino acids, they usually must be cut up into more manageable pieces for analysis. Today, this most commonly is done by using special enzymes called “proteases” that sever the chains at well-known locations. The protease trypsin, for example, cuts proteins at the locations of the amino acids lysine and arginine. Analyzing the residual fragments can identify the original protein. But enzymes are notoriously fussy, demanding fairly tight control of temperature and acidity, and the enzymatic cutting process can be time-consuming, from a matter of hours to days.

For a “radically” different approach, the NIST group turned to a semiconductor material, titanium dioxide. Titanium dioxide is a photocatalyst—when exposed to ultraviolet light its surface becomes highly oxidizing, converting nearby water molecules into hydroxyl radicals, a short-lived, highly reactive chemical species.** In the NIST experiments, titanium dioxide coatings were applied to a variety of typical microanalysis devices, including microfluidic channels and silica beads in a microflow reactor. Shining a strong UV light on the area, in the presence of a protein solution, creates a small “cleavage zone” of hydroxyl radicals that rapidly cut nearby proteins at the locations of the amino acid proline.

Although development work remains to be done, according to the researchers, the NIST photocatalysis technique offers several advantages over conventional enzyme cleavage of proteins. It’s not particularly sensitive to temperature or acidity, and needs no additional reagents other than dissolved oxygen in the solution. It’s a simple arrangement, easy to incorporate into a wide range of instruments and devices, and titanium dioxide, an inorganic material, will last virtually forever in a broad range of conditions—enzymes have to be treated carefully and stored in temperature-controlled environments. The target amino acid, proline, is relatively sparse in most proteins, but it’s found at key locations, such as sharp turns in the molecule, that aid analysis. And it’s fast—in trials with the protein angiotensin I, the team obtained detectable cleavage patterns in as little as 10 seconds.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nist.govAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…