New genetic mutations found that may cause cleft lip/palate

University of Iowa researchers and collaborators have identified new genetic mutations that likely cause the common form of cleft lip and palate

The results could eventually help clinicians predict a family's risk of having more children with the condition. The findings appear in the week of March 5 online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Cleft lip and palate, found in nearly one of every 700 live births worldwide, occurs when tissues that normally form the lip and palate fail to join early in fetal life. The investigation focused on genes in the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, which function in a signaling pathway important in fetal face development, said Bridget Riley, a student in the UI Genetics Ph.D. Program and the study's primary author.

“The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway is interesting because it is involved in many developmental processes, and we were especially interested in how it affects facial development. Prior to this study, the fibroblast growth factors had been looked at in syndromic forms of clefting but had not been examined in non-syndromic forms,” said Riley, whose research team is based in the lab of Jeff Murray, M.D., a professor with multiple UI appointments and a study co-author.

The common form of cleft lip and palate is also known as non-syndromic, as it occurs in isolation and not in association with any known syndrome. The team compared the DNA from 184 people from Iowa and the Philippines had non-syndromic cleft lip and palate with DNA from people without the condition. Riley led the effort that found the mutations in FGF ligands and associated receptors.

Computer modeling of proteins, completed by Moosa Mohammadi, Ph.D., associate professor of pharmacology at New York University School of Medicine, indicated that each mutation would disrupt FGF signaling in a different way. The team will next test the mutant proteins to see if they affect protein function, Riley said.

The researchers estimate that abnormal FGF signaling may account for up to 5 percent of non-syndromic cleft lip and palate cases. Riley emphasized that the findings still need additional study but eventually could have important clinical value through the development of a diagnostic test. The findings could also provide information about FGF signaling in other craniofacial conditions.

“We're now better equipped to look at the factors that cause this birth defect and tackle improved ways to diagnose, treat and, we hope, eventually prevent the condition,” said Murray, who is the Roy J. Carver Chair of Prenatal Health and professor of pediatrics in the UI Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine with joint appointments in pediatric dentistry in the College of Dentistry, biology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and epidemiology in the College of Public Health.

Riley initially presented study results in preliminary form at the plenary session of the annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics held Oct. 10 in New Orleans.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uiowa.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

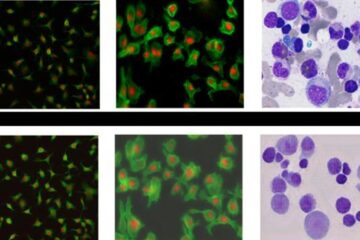

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…