<i>Goldfinger</i> held grain of truth

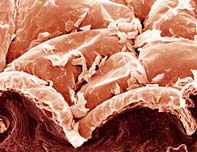

Skin deep: oxygen from the air feeds the epidermis and some of the dermis <br>© SPL <br>

Our skin takes its oxygen straight from the air.

The James Bond movie Goldfinger spawned the urban myth that a person can suffocate if air cannot reach their skin. But the plot contains a grain of truth, new research reveals – our skin gets its oxygen from the atmosphere, not the blood.

Air supplies the top 0.25-0.4 mm of the skin with oxygen, dermatologist Markus Stücker of the Ruhr-University in Bochum, Germany, and his colleagues have found. This is almost 10 times deeper than previous estimates. This zone includes the entire outermost layer of living cells – the epidermis – and some of the dermis below, which contains sweat glands and hair roots.

The finding could change doctors’ approach to skin conditions. Says David Harrison, who studies the use of oxygen by the skin at the University Hospital of North Durham, UK: “Everyone thought that atmospheric oxygen was unimportant, but a significant depth of the skin is supplied from the air.”

Air cut

Diseases of the skin and its blood supply take a heavy toll, particularly on the elderly. The UK National Health Service, for example, spends about £500 million (US$700 million) each year on treating chronic leg ulcers.

“Most physicians think these are due to missing oxygen,” says Stücker. But his finding that skin has free access to all the oxygen it needs suggests instead that ulcers may be caused instead by poor blood supply starving tissues of nutrients.

Harrison thinks that tissue damage could occur when the balance between blood supply and atmospheric oxygen supply breaks down. He points out that medics usually bandage an ulcer, which, by cutting it off from the air, may actually worsen any oxygen shortage.

Air’s oxygenation of skin could also be relevant to diseases in which skin cells divide excessively, such as psoriasis and eczema. Covering the skin can ease these conditions, but no one knows why. Stücker’s finding, coupled with the fact that oxygen boosts cell division, could provide an answer.

Healthy skin that is isolated from the air can compensate by drawing oxygen from the blood, but diseased skin seems to be unable to do this.

Air traffic control

Stücker and his colleagues measured skin breathing by covering a small patch of skin with an oxygen-sensitive membrane. Previous methods were invasive – sticking an electrode into the skin – or involved putting the entire torso, or a limb, into a chamber to measure gas exchange. This hid the large amounts of variation in gas exchange in different areas.

Although the skin relies on air, only 0.4% of the body’s total oxygen needs are supplied this way, the team found. Cutting off the blood supply to the skin had almost no effect on the level of oxygen in the organs. Results were the same for 20-year-old subjects as for 70-year-olds.

References

- Stücker, M. et al. The cutaneous uptake of oxygen contributes significantly to the oxygen supply of human dermis and epidermis. Journal of Physiology, 538, 985 – 994, (2002).

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nature.com/nsu/020211/020211-5.htmlAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

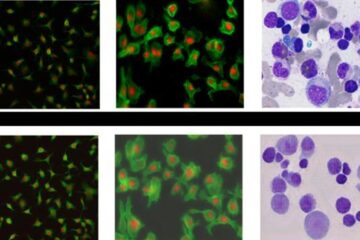

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…