Molecule discovered to be key to pain sensitivity

Sensitivity to pain and the risk of developing chronic pain appear to be influenced by levels of a molecule known to be required for the production of major neurotransmitters. In the November issue of Nature Medicine, an international research team based at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) describes this unexpected role for the molecule called BH4 and their findings that a particular set of variations in a human gene involved in synthesizing the molecule appears to reduce pain sensitivity.

“This is the first evidence of a genetic contribution to the risk of developing neuropathic pain in humans. The pain-protective gene sequence, which is carried by about 20 to 25 percent of the population, appears to be a marker both for less pain sensitivity and a reduced risk for chronic pain,” says senior author Clifford Woolf, MD, PhD, director of the Neural Plasticity Research Group in the MGH Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care. “Identifying those at greater risk of developing chronic pain in response to medical procedures, trauma or diseases could lead to new preventive strategies and potential treatments.”

Previous studies in animals have shown that specific strains or related groups of rodents have significant differences in their risk of developing either neuropathic pain, which results from nerve damage, or inflammatory pain, associated with the immune system's response to injuries or conditions like arthritis. But except for some rare inherited conditions, there has been no evidence that genetics contributed to the risk of neuropathic pain in humans.

The research team had previously used gene chips to find that nerve damage in rats altered the regulation of several hundred genes in associated nerve cells. They began the current study by searching through these genes to find any associated with common metabolic pathways and found that three genes that increased expression in response to nerve damage encoded enzymes involved in the production and recycling of BH4, which is essential for the production of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and nitric oxide. Tests in rat models found that the BH4-synthesizing enzymes were activated in injured sensory neurons and that substances known to inhibit those enzymes reduced pain, acting as analgesics. Directly injecting BH4 or a similar molecule increased the animal's response to several painful stimuli.

As a result of the animal studies, the researchers hypothesized that particular variations of human genes involved in the regulation of BH4 might be associated with different responses to pain. Searching for alterations in the gene for GCH1, the human version of the key BH4-controlling enzyme, they genotyped tissues from 168 patients who had participated in an earlier study of spinal disk surgery. One specific GCH1 haplotype – a set of variations in the gene that are inherited together – was more common in study participants who reported less neuropathic pain in the year after their surgery.

To see if that haplotype had a similar association with other types of pain, the researchers studied almost 400 healthy volunteers, who participated in tests of their response to various slightly painful experimental stimuli. Again, those participants with the protective GCH1 haplotype – which the investigators showed reduces the production of BH4 – also reported less pain, and volunteers with two copies of the protective sequence were even less sensitive to pain.

“Our results tell us that BH4 is a key pain-producing molecule – when it goes up, patients experience pain, and if it is not elevated, they will have less pain,” says Woolf. “The data also suggest that individuals who say they feel less pain are not just stoics but genuinely have inherited a molecular machinery that reduces their perception of pain. This difference results not from personality or culture, but real differences in the biology of the sensory nervous system.

“Now we need to identify what regulates the switching on of BH4-controlling enzymes after nerve injury and how BH4 alters the excitability of pain fibers. We also would like to see whether those with the protective haplotype might participate more frequently in potentially painful activities – such as extreme sports – or if they have reduced levels of pain in arthritis and other common conditions,” he adds. Woolf is the Richard Kitz Professor of Anaesthesia Research at Harvard Medical School.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.mgh.harvard.edu/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

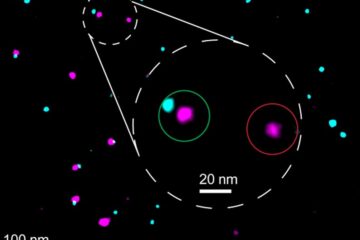

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…