It takes two (or more) to tango: how a web of chromosome interaction can help to explain gene regulation in humans

The two scientists show that chromosomes in the nucleus of metabolically active cells are largely intermingled, and that this physical contact is associated with their gene activity. The researchers propose that chromosomes exist in an intricate network of interactions, which are specific for each cell type, and which result in interactions between genes of different chromosomes. Identification and study of these physical contact points will help scientists to better understand gene regulation in processes as diverse as cancer or human evolution.

The human genome consists of 50,000 to 100,000 genes located within long strands of DNA (like beads in a string) which make up the 23 pairs of chromosomes found in humans. And while the human genome project has helped us to understand better our genetic makeup, the path from the information contained in our genes to the final result, that is a human being, is still poorly understood. Chimpanzees share 96% of our genome but we are undoubtedly very different from them, and scientists believe that much of these differences result from different gene interactions and regulatory mechanisms that allow some genes to be expressed but not others. But how does this happen? Part of the answer to this question, seems to lie in a period of the cellular life cycle called interphase. Interphase is the stage during which the cell is not dividing and is, instead, involved in high metabolic activity: genes are expressed (in a highly regulated manner) leading to the production of a variety of proteins that are found in the different cells in the body. It is also the period when many mutations occur during the duplication of the cell’s DNA material in preparation for cell division. During this phase each chromosome occupies a different area or territory in the nucleus. For a long time it has been believed that these territories were completely separate from each other, but recent data challenge this idea. In fact, not only have movements of chromosomes been observed during this stage, but also a large number of translocations takes place, implying some kind of chromosome proximity. Translocations are mutations which appear when two broken chromosomes are repaired incorrectly resulting in a broken chromosome piece inserted into the wrong chromosome

However, until now studies of the nucleus during interphase failed to show any significant amount of contact between chromosomes. But all this changed with the work of Branco and Pombo, which developed a technique capable of preserve much more efficiently chromosomes’ structure in the nucleus (destruction of chromosome structure turned out to be one of the problems in previous studies) while still allowing their clear visualization.

The researchers used this new technique to study cells of the human system and were amazed to find that chromosomes in these cells showed, contrary to all previous results, an extraordinary level of intermingling, with an average of 46% of each chromosome territory in contact with other chromosomes. Such level of juxtaposition between chromosomes immediately raised the possibility that this physical contact could have an important physiological function. Interestingly, Branco and Pombo also found that the degree of intermingling specific for each pair of chromosomes was directly related to the amount of translocations recorded for that pair. A chromosomal translocation is a potential disease-inducing process since the insertion of a chromosome piece into a different chromosome can lead to aberrant gene expression. This process is particularly dangerous when it affects oncogenes (genes with the potential to induce cancer) as it might lead to cancerous process including several types of leukaemia and lymphomas. The correlation between chromosome contact and translocation observed by Branco and Pombo is very interesting because it can explain, for example, why certain translocations, which can lead to cancer, appear only in some tissues. In fact, it is known that chromosome positioning in the nucleus is specific for each type of cells and consequently, probably also intermingling.

The next step was to understand if gene activity and intermingling were connected. To test this, Branco and Pombo decided to block a crucial step in gene expression only to find that this blocking also led to alterations in the intermingling levels supporting the existence of a link between the two processes. Next, the researchers did the reverse test and activated a gene, again looking for changes in intermingling. To their surprise they were able to clearly see the activated gene, getting into contact (intermingling) with three others chromosomes suggesting that the expression of the activated gene seems to involve some kind of interaction with these other chromosomes. These two experiments confirmed that intermingling is involved in gene expression and most probably not only in human cells.

Gene regulation is a key physiological mechanism. The expression of genes is known to be regulated at many levels but the way nuclear organisation can influence this process is perhaps the one about which less is known. Branco and Pombo’s work is a crucial step to understand this issue by supporting the existence of a network of chromosomes with multiple points of physical contact which creates a functional web, specific for each cell type, of communication between genes of different chromosomes.

There are many important implications for Branco and Pombo’s discovery. Observation of those contact points between chromosomes, by elucidating which areas (and genes) interact will be helpful in many different fields. These range from studies of human evolution and differential gene expression to causes of disease. A good example are cancers that result from abnormal regulation of an oncogene by other genes, that can start to be better understood as scientists become able to “see” exactly which chromosomes (and possibly genes) interact in patients.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

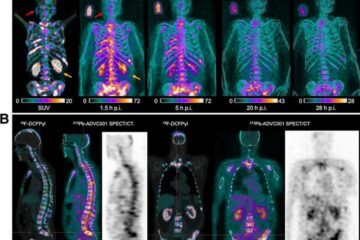

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…