"Laser Tweezers" Permit Penn Researchers to Describe Microscopic Mechanical Properties of Blood Clots

A Better Understanding of Clot Physiology Can Lead to More Effective Therapies

For the first time ever, using “laser tweezers,” the mechanical properties of an individual fiber in a blood clot have been determined by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Their work, led by John W. Weisel, PhD, Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at Penn, and published in this week’s early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides a basis for understanding how the elasticity of the whole clot arises.

Clots are a three-dimensional network of fibrin fibers, stabilized by another protein called factor XIIIa. A blood clot needs to have the right degree of stiffness and plasticity to stem the flow of blood when tissue is damaged, yet be digestible enough by enzymes in the blood so that it does not block blood-flow and cause heart attacks and strokes.

Weisel and colleagues developed a novel way to measure the elasticity of individual fibrin fibers in clots-with and without the factor XIIIa stabilization. They used “laser tweezers”-essentially a laser-beam focused on a microscopic bead ‘handle’ attached to the fibers-to pull in different directions on the fiber.

The investigators found that the fibers, which are long and very thin, bend much more easily than they stretch, suggesting that clots deform in flowing blood or under other stresses primarily by the bending of their fibers.

Weisel likens the structure of a clot composed of fibrin fibers to a microscopic version of a bridge and its many struts. “Knowing the mechanical properties of each strut, an engineer can extrapolate the properties of the entire bridge,” he explains. “To measure the stiffness of a fiber, we used light to apply a tiny force to it and observed it bend in a light microscope, just as an engineer would measure the stiffness of a beam on a macroscopic scale. The mechanical properties of blood clots have been measured for many years, so now we can develop models to relate individual fiber and whole clot properties to understand mechanisms that can yield clots that have vastly different properties.”

He states that these findings have relevance for many areas: materials science, polymer chemistry, biophysics, protein biochemistry, and hematology. “We present the first determination of the microscopic mechanical properties of any polymer of this sort,” says Weisel. “What’s more, our choice of the fibrin clot has particular biological and clinical significance, since fibrin’s mechanical properties are essential for its functions in clotting and also are largely responsible for the pathology of thrombosis that causes most heart attacks and strokes.”

By understanding the microscopic mechanical properties of a clot and how that relates to its observed function within the circulatory system, researchers may be able to make predictions about clot physiology. For example, when clots are not stiff enough, problems with bleeding arise, and when clots are too stiff, there may be problems with thrombosis, which results when clots block the flow of blood.

But how can this knowledge be used to stop bleeding or too much clotting? “Once we understand the origin of the mechanical properties, it will be possible to modulate those properties,” explains Weisel. “If we can change a certain parameter perhaps we can make a clot that’s more or less stiff.” For example, various peptides or proteins, such as antibodies, bind specifically to fibrin, affecting clot structure. The idea would be to use such compounds in people to alter the properties of the clot, so it can be less obstructive and more easily dissolved.

“This paper shows how new technology has made possible a simple but elegant approach to determine the microscopic properties of a fibrin fiber, providing a basis for understanding the origin of clot elasticity, which has been a mystery for more than 50 years,” adds Weisel.

Weisel’s Penn co-authors are Jean-Philippe Collet, Henry Shuman, Robert E. Ledger, and Seungtaek Lee. Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Assistance Publique Hopitaux de Paris, and Parke-Davis. The authors claim no conflicts of interest.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uphs.upenn.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

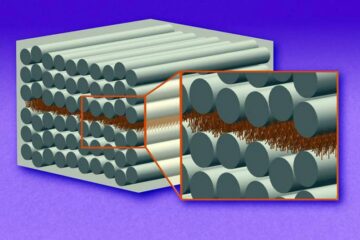

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…

Trash to treasure

Researchers turn metal waste into catalyst for hydrogen. Scientists have found a way to transform metal waste into a highly efficient catalyst to make hydrogen from water, a discovery that…

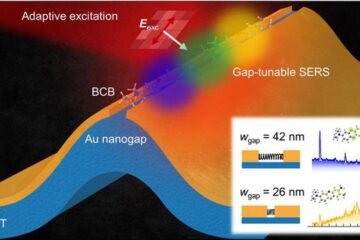

Real-time detection of infectious disease viruses

… by searching for molecular fingerprinting. A research team consisting of Professor Kyoung-Duck Park and Taeyoung Moon and Huitae Joo, PhD candidates, from the Department of Physics at Pohang University…