Structure solved by Scripps scientists shows one way that body controls gene expression

A group of scientists at The Scripps Research Institute has solved the structure of a protein that regulates the expression of genes by controlling the stability of mRNA — an intermediate form of genetic information between DNA genes and proteins.

“Gene expression can be controlled at many levels, ” says Scripps Research Professor Peter Wright, Ph.D., who is chairman of the Department of Molecular Biology and Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Investigator in Medical Research at Scripps Research. “One of them is at the level of the message.”

The structure of the “tandem zinc finger” domain of the regulatory protein TIS11d in complex with a strand of mRNA was solved in the laboratory of Wright and H. Jane Dyson, Ph.D., by Maria A. Martinez-Yamout, Ph.D., of Scripps Research, and Brian P. Hudson, Ph.D., of Rutgers University. This is the first such structure to be solved, and it provides insights into the process of gene regulation at the atomic level.

In next month’s issue of Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, Wright and his colleagues describe the tandem zinc finger — thus called because it contains two finger-like domains that must bind to zinc to fold into its active form. These tandem zinc fingers are a very common motif in mammalian genes, and hundreds of genes in the human genome contain some version of them. This diversity is perhaps indicative of the capability of TZF proteins to specifically recognize a large number of different RNA sequence motifs.

Insights into the workings of the regulatory protein TIS11d are particularly valuable because these proteins are involved in a number of fundamental biological processes, such as inflammation, and are potential targets for therapeutics in diseases where these processes go awry.

The Regulation of Genes at the mRNA Level

Regulation of gene expression in humans and other organisms is a crucial part of biology, and biology has a large repertoire of mechanisms for turning genes on and off. Many of the proteins encoded by genes in human and other genomes specialize in regulating other genes, often in complicated feedback mechanisms.

Shutting off the transcription of a gene — the process whereby a single-stranded piece of messenger RNA (mRNA) is made from a double-stranded piece of DNA — has for decades been recognized by molecular and cell biologists as a crucial way the cell regulates the expression of a gene.

In the last several years, many of these same scientists, including Wright and his colleagues, have been growing aware of the importance of post-transcriptional gene regulation, which occurs at the level of mRNA.

In mammals, once DNA genes are transcribed into mRNAs in the nucleus of a cell, they are usually transported outside the nucleus, where the mRNAs can be “translated” into proteins. At this point, certain regulatory proteins stabilize the mRNA, allowing it to be translated by the cell’s machinery into proteins. Other regulatory proteins destabilize the mRNAs, marking them for degradation by the cell’s machinery.

TIS11d belongs to a common family of regulatory proteins of this latter type. It regulates the levels of many important proteins involved in the body’s inflammatory response, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interferons, by marking the TNF and interferon mRNAs for destruction. With incredible specificity, this protein uses its tandem zinc finger domain to recognize particular sequences of TNF and interferon mRNA.

By solving the structure, Wright and his colleagues revealed for the first time in atomic detail exactly how this recognition occurs.

The TIS11d protein basically mimics the base-pairing that takes place in DNA by using its tandem zinc finger domains to bind to the mRNA. Following the same principle that two strands of DNA use to bind to each other, the TIS11d protein binds to the mRNA by forming hydrogen bonds with the Watson-Crick edges of the mRNA.

“It was remarkable to see how these tiny structures [work],” says Wright.

The research article “Recognition of the mRNA AU-rich element by the zinc finger domain of TIS11d” is authored by Brian P. Hudson, Maria A. Martinez-Yamout, H. Jane Dyson, and Peter E. Wright and appears in the March 2004 issue of Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and The Skaggs Institute for Research.

About The Scripps Research Institute

The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, is one of the world’s largest, private, non-profit biomedical research organizations. It stands at the forefront of basic biomedical science that seeks to comprehend the most fundamental processes of life. Scripps Research is internationally recognized for its research into immunology, molecular and cellular biology, chemistry, neurosciences, autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular diseases and synthetic vaccine development.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.scripps.edu/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

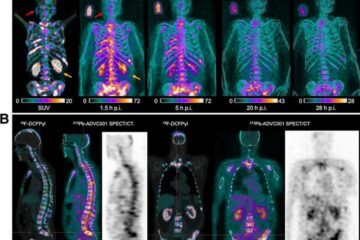

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…