UT Southwestern researchers define regions of human genes highly prone to mutation

Dr. Harold "Skip" Garner, foreground, and John W. "Trey" Fondon III have taken the first step in defining the sites in human genes most prone to mutation.

UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas researchers have taken the first step in defining the sites in human genes most prone to mutation, which eventually could lead to discovery of the genetic bases of many human diseases.

Their work will appear in an upcoming issue of the journal Gene and is currently available online.

Dr. Harold “Skip” Garner, professor of biochemistry and internal medicine, and his colleagues made their discovery while mining databases of coding single nucleotide polymorphisms (cSNPs) held by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, the SNP Consortium, the National Cancer Institute and the Institute of Medical Genetics at Cardiff, Wales. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common and simplest form of genetic mutation in the human genome.

In their analysis, the researchers showed that a large fraction of human cSNPs occur at only a few distinctive and usually recurrent DNA sequence patterns. However, such events within the genome account for a disproportionate amount of all gene point mutations.

Developing an association between phenotype (the outward, physical manifestation) and genotype (the internally coded, inheritable information) is vital toward understanding and identifying indications of disease.

“This discovery can be used to essentially define the likelihood of one gene to mutate relative to others as a function of both time and environment,” said Monica M. Horvath, molecular biophysics graduate student and co-author. “cSNP trends are critical to quantify in order to develop hypotheses regarding the complexity and range of mutational mechanisms that generate both genome diversity and disease.”

The next phase, Ms. Horvath said, is to employ both experimental and computational tests to benchmark how well these trends can predict mutations not yet found in the human genome.

“What I like the most about this work is that it shows that as proteins evolve, natural selection has considerable latitude, not only in determining the amino acid sequence of a protein, but also in determining how frequently and severely to break it,” said John W. Fondon III, molecular biophysics graduate student and contributing author.

“What Ms. Horvath has done is to essentially crack the code within the code – to reveal how selection exploits redundancy within the genetic code to specify whether a particular amino acid letter in a protein is written in stone, with ink, or in wet sand at low tide.”

An important application of this research is that with enhanced knowledge of where mutations are most likely to occur, medical geneticists can take more aggressive approaches to discover the genetic basis of many human diseases.

“We know the genome is very big, and there currently is no technology to remeasure every single letter of this 3-billion-letter code,” said Dr. Garner.

“A very significant byproduct of this research into the complex interplay between mutation and selection is that Ms. Horvath has revealed some clear rules that can contribute to the design and execution of genetic association studies. This will become an important component of the solution to the currently intractable problems presented by complex diseases that involve many genes.”

The research was supported by a National Institute of Health grant, Program in Genomic Applications grant, the Biological Chemical Countermeasures program of The University of Texas and the state of Texas Advanced Technology Program.

Media Contact: Scott Maier

214-648-3404

or e-mail: scott.maier@utsouthwestern.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://irweb.swmed.edu/newspub/newsdetl.asp?story_id=628All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

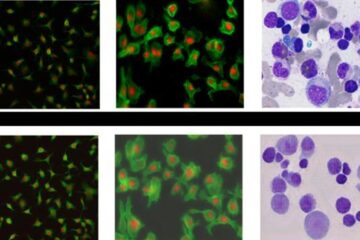

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…