DNA unzipping found to take at least two proteins, not one alone

A companion-less protein stuck during DNA unzipping <br>Photo courtesy of Taekjip Ha <br>

Using an optical fluorescence microscope to monitor enzyme activity, researchers at three universities have solved a long-running mystery. It takes at least two proteins, working in an unstable tandem, to unzip two strands of DNA.

Their newly designed approach, which focuses on the activity of single molecules, also showed — for the first time — that if one protein falls away, the process stops. Unless another climbs aboard, DNA reverts to its zipped state.

The technique, which offers a new way to study activities of many other proteins in general, and the new findings that clarify how DNA unwinds, will be published Thursday (Oct. 10) in the journal Nature. The principal investigator of the research is Taekjip Ha, professor of physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“Our study is unique in that we were able to look at the activity of single molecules and correlate how many participate in the process when the DNA is being unzipped or not,” Ha said. “The reason we like to study a molecule alone rather than a bunch of molecules together is because each is on its own time clock.”

The findings involve a class of DNA motor proteins called helicases, which when defective are linked to genetic diseases such as Bloom syndrome, which carries an increased risk of cancer, and Werner syndrome (premature aging). Viruses, including the hepatitis C virus, import their own form of these proteins to infect their hosts.

Helicases separate strands of DNA. They travel along DNA highways, powered by ATP, a fuel molecule. For many years, scientists have argued whether it takes a single protein or multiple proteins to unzip DNA.

“The primary evidence for the ability of a single molecule to unzip DNA was based on the ability of the molecule as one monomer to move along a single strand,” Ha said.

“This is true, but it had been extrapolated from that knowledge that this should be enough to move along and separate the two strands,Ó Ha said. “Our study shows that that is not true. A single helicase can move along the single-strand tail of a DNA, but once it hits the junction of the one-way and two-way streets, it cannot go any further. It will disassociate at the junction unless you have another coming in to bind to it.”

Ha and colleagues studied the helicases found in E-coli. They used the single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technique that Ha and colleagues had created. Fluorescent dye molecules were applied as probes to defined positions on each biological molecule. Using their microscope, they measured energy transfer efficiency from each DNA during helicase binding and movement. Red or green fluorescence signals appeared and disappeared, indicating distances between the probes during unzipping.

“The unwinding can begin and then stop in the middle of the process,” Ha said. “Think of a little car moving along a street until it comes to a barrier. It cannot go any farther until another car comes and combines with it to become a monster truck. Then it goes on down the street, but the combination is not stable. One vehicle can fall off, and what’s left gets stuck. This is the first time these pauses have been seen, and we have deduced the mechanism: The piece that makes the monster truck breaks off.

Eventually it may be possible to develop drugs to help control the activity of disease-related helicases in human cells and turn them off in viruses, Ha said. The challenge will be to target only the viral versions so the host helicases are not damaged.

Authors were Ha and Ivan Rasnik, a postdoctoral researcher at Illinois; Wei Cheng, George H. Gauss and Timothy M. Lohman of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis; and Hazen P. Babcock and Steven Chu of Stanford University.

The Searle Scholars Program, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, the private Research Corp. and the University of Illinois Research Board funded Ha’s research. The NSF and Air Force Office of Scientific Research also provided funding to Chu. The NIH supported Lohman.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

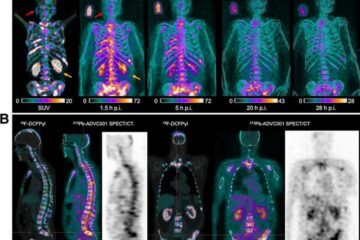

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…