A New Way to Think About Earth's First Cells

A team of researchers at Harvard University have modeled in the laboratory a primitive cell, or protocell, that is capable of building, copying and containing DNA.

Since there are no physical records of what the first primitive cells on Earth looked like, or how they grew and divided, the research team's protocell project offers a useful way to learn about how Earth's earliest cells may have interacted with their environment approximately 3.5 billion years ago.

The protocell's fatty acid membrane allows chemical compounds, including the building blocks of DNA, to enter into the cell without the assistance of the protein channels and pumps required by today's highly developed cell membranes. Also unlike modern cells, the protocell does not use enzymes for copying its DNA.

Supported with funding from the National Science Foundation and led by Jack W. Szostak of the Harvard Medical School, the research team published its findings in the June 4, 2008, edition of the journal Nature's advance online publication.

“Szostak's group took a creative approach to this research challenge and made a significant contribution to our understanding of small molecule transport through membranes,” said Luis Echegoyen, director of the NSF Division of Chemistry. “This is a great outcome of NSF's support of basic research.”

Some scientists have proposed that ancient hydrothermal vents may have been sites where prebiotic molecules–molecules made before the origin of life, such as fatty acids and amino acids–were formed. An animation (accessible at upper right) created by Janet Iwasa of the Szostak Laboratory shows a theoretical scenario in which fatty acids are formed on the surface of minerals deep underground, and then brought to the surface by the eruption of a geyser.

When fatty acids are in an aqueous environment, they spontaneously arrange so that their hydrophilic, or water-loving, “heads” interact with the surrounding water molecules and their hydrophobic, or water-fearing, “tails” are shielded from the water, resulting in the formation of tiny spheres of fatty acids called micelles.

Depending upon chemical concentrations and the pH of their environment, micelles can convert into layered membrane sheets or enclosed vesicles. Researchers commonly use vesicles to model the cellular membranes of protocells. A second animation created by Iwasa (accessible at lower right) shows how vesicles may have been formed.

When the team started its work, the researchers were not sure that the building blocks required for copying the protocell's genetic material would be able to enter the cell.

“By showing that this can happen, and indeed happen quite efficiently, we have come a little closer to our goal of making a functional protocell that, in the right environment, is able to grow and divide on its own,” said Szostak.

Co-authors of the Nature paper include Sheref S. Mansy, Jason P. Schrum, Mathangi Krishnamurthy, Sylvia Tobe and Douglas A. Treco of the Szostak Laboratory.

The research was supported by NSF Division of Chemistry award number 0434507. Jack W. Szostak was also supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Exobiology Program award number EXB02-0031-0018. Sheref S. Mansy was supported by National Institutes of Health award number F32 GM07450601.

Funding for Exploring Life's Origins Web site project was provided by NSF award number 0610117.

Media Contacts

Jennifer A. Grasswick, NSF (703) 292-4972 jgrasswi@nsf.gov

Joshua A. Chamot, NSF (703) 292-7730 jchamot@nsf.gov

Program Contacts

Katharine J. Covert, NSF (703) 292-4950 kcovert@nsf.gov

Principal Investigators

Jack W. Szostak, Harvard Medical School (617) 726-5981 szostak@molbio.mgh.harvard.edu

Related Websites

Szostak Laboratory: http://genetics.mgh.harvard.edu/szostakweb/

Exploring Life's Origins: http://exploringorigins.org/

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency that supports fundamental research and education across all fields of science and engineering, with an annual budget of $5.92 billion. NSF funds reach all 50 states through grants to over 1,700 universities and institutions. Each year, NSF receives about 42,000 competitive requests for funding, and makes over 10,000 new funding awards. The NSF also awards over $400 million in professional and service contracts yearly.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

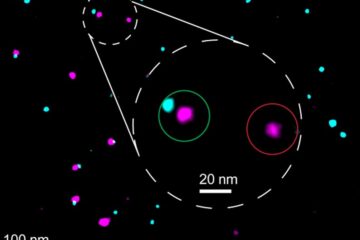

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…