Powerful gene-editing tool appears to cause off-target mutations in human cells

In the past year a group of synthetic proteins called CRISPR-Cas RNA-guided nucleases (RGNs) have generated great excitement in the scientific community as gene-editing tools.

Exploiting a method that some bacteria use to combat viruses and other pathogens, CRISPR-Cas RGNs can cut through DNA strands at specific sites, allowing the insertion of new genetic material. However, a team of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) researchers has found a significant limitation to the use of CRISPR-Cas RGNs, production of unwanted DNA mutations at sites other than the desired target.

“We found that expression of CRISPR-Cas RGNs in human cells can have off-target effects that, surprisingly, can occur at sites with significant sequence differences from the targeted DNA site,” says J. Keith Joung, MD, PhD, associate chief for Research in the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Department of Pathology and co-senior author of the report receiving online publication in Nature Biotechnology. “RGNs continue to have tremendous advantages over other genome editing technologies, but these findings have now focused our work on improving their precision.”

Consisting of a DNA-cutting enzyme called Cas 9, coupled with a short, 20-nucleotide segment of RNA that matches the target DNA segment, CRISPR-Cas RGNs mimic the primitive immune systems of certain bacteria. When these microbes are infected by viruses or other organisms, they copy a segment of the invader's genetic code and incorporate it into their DNA, passing it on to future bacterial generations. If the same pathogen is encountered in the future, the bacterial enzyme called Cas9, guided by an RNA sequence the matches the copied DNA segment, inactivates the pathogen by cutting its DNA at the target site.

About a year ago, scientists reported the first use of programmed CRISPR-Cas RGNs to target and cut specific DNA sites. Since then several research teams, including Joung's, have succesfully used CRISPR-Cas RGNs to make genomic changes in fruit flies, zebrafish, mice and in human cells – including induced pluripotent stem cells which have many of the characteristics of embryonic stem cells. The technology's reliance on such a short RNA segment makes CRISPR-Cas RGNs much easier to use than other gene-editing tools called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and RGNs can be programmed to introduce several genetic changes at the same time.

However, the possibility that CRISPR-Cas RGNs might cause additional, unwanted genetic changes has been largely unexplored, so Joung's team set out to investigate the occurrence of “off-target” mutations in human cells expressing CRISPR-Cas RGNs. Since the interaction between the guiding RNA segment and the target DNA relies on only 20 nucleotides, they hypothesized that the RNA might also recognize DNA segments that differed from the target by a few nucleotides.

Although previous studies had found that a single-nucleotide mismatch could prevent the action of some CRISPR-Cas RGNs, the MGH team's experiments in human cell lines found multiple instances in which mismatches of as many as five nucleotides did not prevent cleavage of an off-target DNA segment. They also found that the rates of mutation at off-target sites could be as high or even higher than at the targeted site, something that has not been observed with off-target mutations associated with ZFNs or TALENs.

“Our results don't mean that RGNs cannot be important research tools, but they do mean that researchers need to account for these potentially confounding effects in their experiments. They also suggest that the existing RGN platform may not be ready for therapeutic applications,” says Joung, who is an associate professor of Pathology at Harvard Medical School. “We are now working on ways to reduce these off-target effects, along with methods to identify all potential off-target sites of any given RGN in human cells so that we can assess whether any second-generation RGN platforms that are developed will be actually more precise on a genome-wide scale. I am optimistic that we can further engineer this system to achieve greater specificity so that it might be used for therapy of human diseases.”

Jeffry D. Sander, PhD, of the MGH Molecular Pathology Unit is co-senior author of the Nature Biotechnology report. Additional co-authors are lead author Yanfang Fu, PhD; Jennifer Foden, Cyd Khayter, Morgan Maeder and Deepak Reyon, PhD, all of MGH Molecular Pathology. Support for the study includes National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director's Pioneer Award DP1 GM105378; NIH grants R01 GM088040 and P50 HG005550, DARPA grant W911NF-11-2-0056, and the Jim and Ann Orr MGH Research Scholar Award.

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $775 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine. In July 2012, MGH moved into the number one spot on the 2012-13 U.S. News & World Report list of “America's Best Hospitals.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.massgeneral.org/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

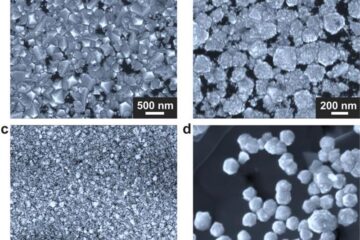

Making diamonds at ambient pressure

Scientists develop novel liquid metal alloy system to synthesize diamond under moderate conditions. Did you know that 99% of synthetic diamonds are currently produced using high-pressure and high-temperature (HPHT) methods?[2]…

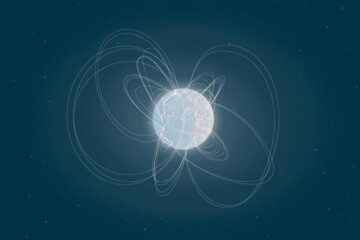

Eruption of mega-magnetic star lights up nearby galaxy

Thanks to ESA satellites, an international team including UNIGE researchers has detected a giant eruption coming from a magnetar, an extremely magnetic neutron star. While ESA’s satellite INTEGRAL was observing…

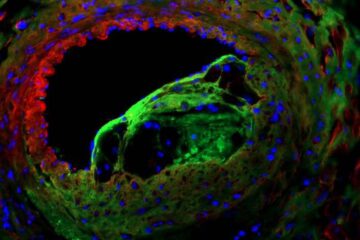

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…