Penn Team Links Schizophrenia Genetics to Disruption in How Brain Processes Sound

Now, three labs at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have come together using electrophysiological, anatomical, and immunohistochemical approaches – along with a unique high-speed imaging technique – to understand how schizophrenia works at the cellular level, especially in identifying how changes in the interaction between different types of nerve cells leads to symptoms of the disease. The findings are reported this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our work provides a model linking genetic risk factors for schizophrenia to a functional disruption in how the brain responds to sound, by identifying reduced activity in special nerve cells that are designed to make other cells in the brain work together at a very fast pace” explains lead author Gregory Carlson, PhD, assistant professor of Neuroscience in Psychiatry. “We know that in schizophrenia this ability is reduced, and now, knowing more about why this happens may help explain how loss of a protein called dysbindin leads to some symptoms of schizophrenia.”

Previous genetic studies had found that some forms of the gene for dysbindin were found in people with schizophrenia. Most importantly, a prior finding at Penn showed that the dysbindin protein is reduced in a majority of schizophrenia patients, suggesting it is involved in a common cause of the disease.

For the current PNAS study, Carlson, Steven J. Siegel, MD, PhD, associate professor of Psychiatry, director of the Translational Neuroscience Program; and Steven E. Arnold, MD, director of the Penn Memory Center, used a mouse with a mutated dysbindin gene to understand how reduced dysbindin protein may cause symptoms of schizophrenia.

The team demonstrated a number of sound-processing deficits in the brains of mice with the mutated gene. They discovered how a specific set of nerve cells that control fast brain activity lose their effectiveness when dysbindin protein levels are reduced. These specific nerve cells inhibit activity, but do so in an extremely fast pace, essentially turning large numbers of cells on and off very quickly in a way that is necessary to normally process the large amount of information travelling into and around the brain.

Other previous work at Penn in the lab of Michael Kahana, PhD has shown that in humans the fast brain activity that is disrupted in mice with the dysbindin mutation is also important for short-term memory. This type of brain activity is reduced in people with schizophrenia and resistant to current therapy. Taken as a whole, this work may suggest new avenues of treatment for currently untreatable symptoms of schizophrenia, says Carlson.

Additional co-authors are: Konrad Talbot, Tobias B. Halene, Michael J. Gandal, Hala A. Kazi, Laura Schlosser, Quan H. Phung, and Raquel E. Gur, all from the Department of Psychiatry at Penn.

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4 billion enterprise.

Penn's Perelman School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools and among the top 10 schools for primary care. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $507.6 million awarded in the 2010 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania — recognized as one of the nation's top 10 hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; and Pennsylvania Hospital – the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Penn Medicine also includes additional patient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2010, Penn Medicine provided $788 million to benefit our community.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

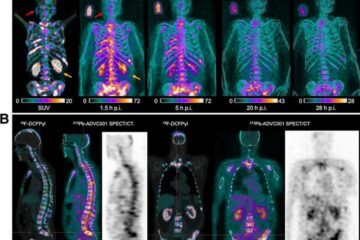

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…