Peanut worms are annelids

Sipunculus nudus of the group of Sipunculidae with a length of about 8 centimeters. photo/©: Dr Anja Schulze, Texas A&M University at Galveston, USA<br>

Recent molecular phylogenetic analysis has shown that the marine animals known as peanut worms are not a separate phylum, but are definitely part of the family of annelids, also known as segmented worms. This is a classification that seemed questionable in the past in view of the fact that peanut worms – or the Sipunculidae, to give them their scientific name – have neither segments nor bristles.

The latter are considered typical characteristics of annelids, which include more than 16,500 identified species and to which our common earthworm belongs. “Our molecular data clearly demonstrates that there is no doubt anymore that the Sipunculidae should be classified as members of these segmented worms,” explains Dr Bernhard Lieb of the Institute of Zoology at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU). The results were obtained as part of a broad study in which the phylogenetic development and relationships within the phylum Annelida were analyzed in terms of basic molecular biology to be then re-evaluated. Participating in the project are the universities of Osnabrück, Potsdam, Mainz, and Leipzig, together with the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Genetics in Berlin. The results have now been published online in the journal Nature.

“The relationships between the various annelids with regard to both morphological and molecular biological aspects have been a matter of dispute,” states Lieb. Segmented worms are the most prevalent of marine macrofauna – their habitat ranges from tidal zones to the deep oceans. Usually, they have been divided into two main classes: the Clitellata, which have few bristles, e.g. earthworms, and leeches on the one hand and the Polychaeta, literally the 'many bristled', on the other hand. The evolutionary and deep branching patterns of annelid lineage are still the subject of on-going scientific debate, although it has become increasingly clear that other groups that had previously been classified separately, such as peanut worms and beard worms, are actually members of this phylum. By means of identifying some 48,000 amino acid positions in 34 different representatives of the phylum Annelida, the research group headed by the universities of Osnabrück and Potsdam has put together the hitherto most detailed database for the family of segmented worms. This has enabled the group to re-evaluate and reconstruct the phylogenetic interrelationships and evolution of this extensive and highly diverse group of animals.

The molecular data on Sipunculus nudus – the peanut worm – gathered by the team in Mainz led by Bernhard Lieb shows that the genetic characteristics of the worm, which lives in sand and silt at the bottom of the sea, clearly indicates that it is a member of the annelid family. In evolutionary terms the peanut worm is likely to be a basal group that diverged very early during evolution. It is conjectured on the basis of the sparse fossil record that the annelids first appeared in the Cambrian Period, roughly 550-490 million years ago. “We assume that segmentation was a very early characteristic of the annelids and that the peanut worm has lost its segmentation during the course of evolution,” clarifies Lieb.

Primarily, new DNA sequencing technologies, so-called next-generation sequencing (NGS), made such comprehensive genetic investigations become possible. The Illumina Hiseq2000 sequencer recently acquired by the Institute of Genetics at JGU can analyze vast amounts of data, and sequence up to 200 gigabases of DNA per run within a single week. This means that whole genomes can be sequenced in a relatively short time, opening up completely new avenues for wide-ranging research.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Combatting disruptive ‘noise’ in quantum communication

In a significant milestone for quantum communication technology, an experiment has demonstrated how networks can be leveraged to combat disruptive ‘noise’ in quantum communications. The international effort led by researchers…

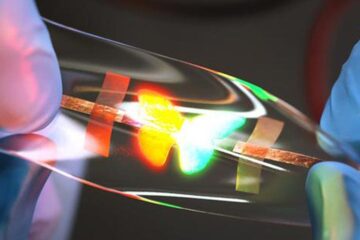

Stretchable quantum dot display

Intrinsically stretchable quantum dot-based light-emitting diodes achieved record-breaking performance. A team of South Korean scientists led by Professor KIM Dae-Hyeong of the Center for Nanoparticle Research within the Institute for…

Internet can achieve quantum speed with light saved as sound

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen’s Niels Bohr Institute have developed a new way to create quantum memory: A small drum can store data sent with light in its sonic…