Organized chaos in the enzyme complex: surprising insights and new perspectives

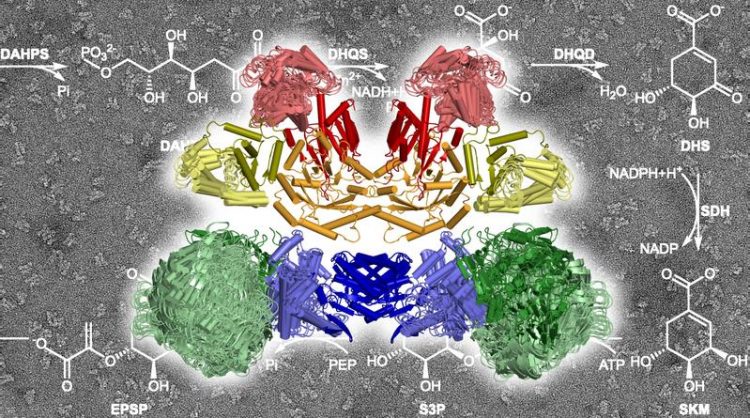

The ten enzymatic components of the AROM complex at work, catalyzing the chemical reactions sketched in the background. Marcus Hartmann 2020

In textbooks, metabolic pathways always look a bit like assembly-line work. One enzyme follows another – like pearls on a string. Intermediate products are removed or passed on from one station to another.

“However, in the cell, this often does not happen in such an orderly fashion,” says Marcus Hartmann, Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology. “The individual components of a metabolic pathway can be located in different areas within the cell, and in most cases it is not understood, if and how they come together to form ordered structures.”

Anyone who wants to understand the function and dynamics of metabolic pathways must therefore also look into the interaction and hierarchies of the individual components. This is the only way to grasp the overall picture.

With this in mind, Hartmann and his team have examined an otherwise well-investigated metabolic pathway: The shikimate pathway. It occurs in plants and microorganisms, including pathogenic fungi and parasitic protists such as the pathogens that cause toxoplasmosis or malaria.

One of its tasks is to synthesize the precursors of the amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan, which are essential in animals and humans. This pathway has recently also gained attention as the target of the notorious herbicide glyphosate.

For the researchers from Tübingen it was of special interest that, while the majority of enzymes of the shikimate pathway are present individually in plant and bacterial cells, in fungi and protists five of the seven components are combined in a large enzyme complex known as AROM. “We wanted to know how this large complex is structured and what the advantages of its architecture might be,” says Hartmann. “For example, if catalysis is more efficient in this complex.”

The scientists succeeded in solving a crystal structure of the entire protein complex.

They found that the five enzyme components, each in two copies, assemble into a compact structure with a total of ten components in a very small space. “We did not expect such a compact architecture,” says Hartmann. “Many enzymes of the shikimate pathway actually need quite a lot of elbow-room for their work.”

Thanks to its ingenious architecture, however, the available space in the AROM complex is sufficient. Although the crystal structure only represents a static snapshot of the complex, “the individual components are so well studied that we can simulate in a computer model how they move within the complex,” explains the scientist.

It turned out that the necessary liberty of action for the individual enzymes is tailored in such a way that they can move independently of each other without collisions. “We actually do not have evidence for any coordination of the individual enzyme motions,” says Harshul Arora Verasztó, first author of the study. “It is more like organized chaos.”

Further investigations have shown that a mere clustering of enzymes – to form the AROM complex – is not sufficient not provide a catalytic advantage for the shikimate pathway of fungi and protists – at least on the basis of the present data. “A comparison under laboratory conditions has shown that the throughput of the complex is not higher than that of the scattered individual enzymes,” says Hartmann. “For biotechnologists, who are trying to optimize the efficiency of catalytic cascades via the clustering of enzymes, this might be surprising news.”

In the first place, the results obtained by the Tübingen scientists contribute to basic research – to gain insights into how enzymes and in particular enzyme complexes function in metabolic pathways. However, they also open up completely new perspectives for drug discovery. “In this regard, the tight arrangement of the particularly flexible enzyme components within the AROM complex is highly interesting,” explains Hartmann.

In most cases, drugs attack at the catalytic centers, at the sites where enzymes perform their reactions. “For the AROM complex, it is conceivable to develop drugs that act like a wedge between the enzymatic components to block them”. This approach could lead to the development of inhibitors that only work on fungi or protists, such as the pathogens causing toxoplasmosis or malaria, but do not impair the shikimate pathway of plants and bacteria.

Dr. Marcus Hartmann

Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology

Phone: +49 (0)7071 601 323

e-Mail: marcus.hartmann@tuebingen.mpg.de

Verasztó HA, Logotheti M, Albrecht R, et al. Architecture and functional dynamics of the

pentafunctional AROM complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. DOI 10.1038/s41589-020-0587-9

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…