Discovery of a new way of developing resistance

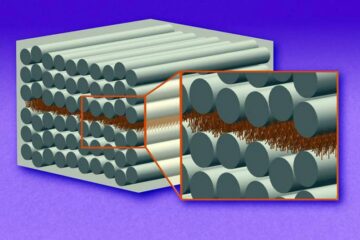

From a colony of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (middle, orange), groups that produce an antibiotic (white) and groups that are resistant to this antibiotic (periphery, yellow) gradually develop. (Photo: Daniel Lopez)

Many infections that used to mean certain death can nowadays usually be overcome quickly by taking a few tablets. This is all thanks to antibiotics. So, it is all the more disturbing to physicians and patients alike that many pathogenic bacteria are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotics.

This is particularly problematic in hospitals when bacteria spread that have become resistant to several antibiotics at the same time: these pathogens can be life-threatening for older and vulnerable patients. Sometimes such bacteria can be found in so-called biofilms on medical instruments or implants: they settle there in relatively large colonies inside a shared protective shell, which makes them even less receptive to drugs.

How is it that bacteria are becoming increasingly resistant? “It is because they come into contact with antibiotics too often and develop defense mechanisms,” according to the scientifically accepted explanation. Resistance is partly encouraged by the fact that physicians prescribe antibiotics too frequently and often even without good reason and by the fact that the agents are often mixed with food prophylactically in factory farming.

Competition between bacteria leads to resistance

Würzburg researchers have now discovered another way in which bacteria can become resistant – and surprisingly it has nothing to do with antibiotics used by humans. “Resistance already arises when competing bacteria live together in large numbers and in confined spaces,” says Dr. Daniel Lopez from the Research Center for Infectious Diseases at the University of Würzburg.

The scientists discovered this during experiments with Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, which are not resistant to antibiotics. They kept the bacteria under the conditions that prevail in a biofilm, i.e. numerous individuals in a confined space with a limited supply of nutrients.

A small evolution takes place in the biofilm

In this environment the Staphylococci become rivals and experience a kind of small-scale evolution: individual bacteria that are suddenly able to produce antibiotics through spontaneous mutations have the advantage. They keep the competition at a distance and multiply successfully. It is normal for bacteria to produce antibiotics themselves: even “in the wild” they use these agents to assert themselves against other bacteria, and many commonly prescribed antibiotics are derived from bacterial antibiotics.

In the biofilm created by the Würzburg researchers, the initial bacteria did not meekly surrender to this attack: they in turn developed mechanisms to defend themselves against the antibiotics, rendering themselves resistant. After just five days, there were three very distinctive groups of bacteria in the biofilm: the “harmless” original bacteria, the antibiotics producers, and the antibiotic-resistant group. This is reported by the Würzburg researchers in the current issue of the journal “Cell”.

Biofilms as breeding grounds for resistance

“Biofilms can therefore be breeding grounds for resistance without coming into contact with antibiotics from outside,” says Daniel Lopez. Consequently, hospitals should take even more care than they already do to prevent and combat biofilms. As their next step, the Würzburg researchers want to find out further details about what happens in biofilms. They are particularly interested in whether and how the ominous resistance development processes can be prevented.

“Evolution of Resistance to a Last-Resort Antibiotic in Staphylococcus aureus via Bacterial Competition”, Gudrun Koch, Ana Yepes, Konrad U. Förstner, Charlotte Wermser, Stephanie T. Stengel, Jennifer Modamio, Knut Ohlsen, Kevin R. Foster, and Daniel Lopez, Cell, Vol. 158, Issue 5, p1060–1071, 28. August 2014, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.046

Contact

Dr. Daniel Lopez, leader of the junior research group “Bacterial Cell Differentiation”, Research Center for Infectious Diseases, University of Würzburg, T +49 (0)931 31-83831, daniel.lopez@uni-wuerzburg.de

Daniel Lopez’s homepage: http://www.imib-wuerzburg.de/research/lopez/group-leader

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…

Trash to treasure

Researchers turn metal waste into catalyst for hydrogen. Scientists have found a way to transform metal waste into a highly efficient catalyst to make hydrogen from water, a discovery that…

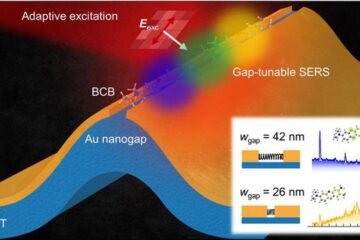

Real-time detection of infectious disease viruses

… by searching for molecular fingerprinting. A research team consisting of Professor Kyoung-Duck Park and Taeyoung Moon and Huitae Joo, PhD candidates, from the Department of Physics at Pohang University…