Cells eat themselves into shape – Specialised endocytocis consumes membrane tendrils

The study, published today in Nature Communications, could help explain how the cells on your skin become different from those that line your stomach or intestine.

“We’re the first to show that endocytosis really drives changes in cell shape by directly remodelling the cell membrane,” says Stefano De Renzis, who led the work.

De Renzis and colleagues made the discovery by studying the fruit fly Drosophila, which starts life as a sac. The fly’s embryo is initially a single large cell, inside which nuclei divide and divide, until, at three hours old, the cell membrane moves in to surround each nucleus, so that in about an hour the embryo goes from one to 6000 cells.

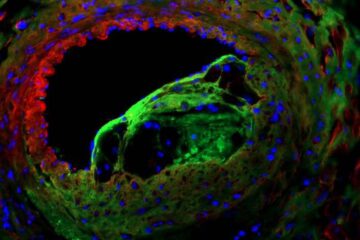

As this happens, cells change shape. The cell membrane starts off with lots of finger-like tendrils sticking out of the embryo, and in about 10 minutes it smoothes down to a flat surface, like a rubber glove transforming into a round balloon.

The EMBL scientists found that, for this quick shape-shift to happen, the cells ‘eat up’ their finger-like offshoots. And, to quickly take up all that excess membrane, cells adapt their ‘feeding strategy’. Instead of bending a little pouch of membrane inwards and eventually detaching it into the cell as a round pod, or vesicle, the fruit fly embryo’s cells suck in long tubes of membrane. Once inside the cell, those tubes are then processed into smaller vesicles.

The findings, which include uncovering one of the key molecules involved, provide a new way of thinking about how cells take on the shape required to perform different tasks – and not only in fruit flies.

“This outward-facing – or apical – surface is the main difference between different kinds of epithelial cell,” says De Renzis. “The cells on your skin are smooth, but the ones lining your intestine have lots of ‘fingers’ like our fly embryos, and we know for instance that some bowel diseases involve problems in those ‘fingers’.”

For this work, Piotr Fabrowski in De Renzis’ lab developed a new strategy for imaging the fruit fly embryo and Aleksandar Necakov, a joint post-doctoral fellow in the De Renzis and John Briggs labs at EMBL, combined light and electron microscopy to see how different the swallowed membrane tubes are from the vesicles usually formed in endocytosis.

Published online in Nature Communications on 7 August 2013.

For images, videos and for more information please visit: www.embl.org/press/2013/130807_Heidelberg.

The videos accompanying this release are also available on the EMBL YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/emblmedia.

Policy regarding use

EMBL press and picture releases including photographs, graphics and videos are copyrighted by EMBL. They may be freely reprinted and distributed for non-commercial use via print, broadcast and electronic media, provided that proper attribution to authors, photographers and designers is made.

Sonia Furtado Neves

EMBL Press Officer

Meyerhofstr. 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)6221 387 8263

Fax: +49 (0)6221 387 8525

sonia.furtado@embl.de

www.embl.org

Keep up-to-date with EMBL Research News at: www.embl.org/news

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.embl.orgAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…

Decisive breakthrough for battery production

Storing and utilising energy with innovative sulphur-based cathodes. HU research team develops foundations for sustainable battery technology Electric vehicles and portable electronic devices such as laptops and mobile phones are…