Broccoli & co.: mustard oils as chemical mace

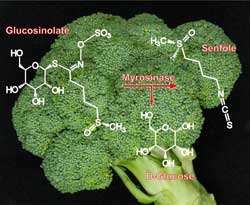

When caterpillars or other hungry insects feed on glucosinolate-containing plants like broccoli, the glucosinolates get in contact with the enzyme myrosinase, that releases mustard oils. These ward off the insects. Picture: Dietmar Geiger<br>

Plants produce a large variety of substances that are often highly prized by humans, such as caffeine and essential oils. Many substances derived from plants add special flavors to meals, and quite a number are regarded as health-promoting. This also applies to mustard oils, which make mustard spicy and give brassicas their unique aroma.

Mustard oils are reputed to be able to prevent cancer. There are various signs to support this notion. “For example, it is known that the constituents of broccoli kill off the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which can trigger stomach ulcers and cancer,” says Professor Rainer Hedrich, plant scientist at the University of Würzburg.

Mustard oils as protection against enemies

Of course, plants do not synthesize such special constituents to protect humans. Instead, they use them to keep microbes and other enemies at bay. Often, they only use their chemical mace in an emergency. The pungent and spicy mustard oils, for instance, are only produced if the plant is injured, say, by an insect munching on it. Only then do the precursors of the mustard oils, the glucosinolates, come into contact with an enzyme that releases the mustard oils. This effect is familiar to anyone who has ever bitten into a radish.

Hungry insects tend to seek out the nutritious leaves and seeds. So, it is no wonder that the plant accumulates particularly large quantities of glucosinolates in these parts. The leaves can produce the deterrents themselves, but the maturing seeds cannot. “They have to import the glucosinolates, and this is not possible without special transport proteins,” says Professor Dietmar Geiger, plant physiologist at the University of Würzburg.

Prospects for agriculture

Until recently, virtually nothing was known about these vital transporters and their genes. But a research team from Copenhagen, Würzburg, and Madrid has now identified them. The results have been published in the journal “Nature”, giving them great prominence because they could have a far-reaching impact on agriculture.

Hedrich explains: “This paves the way for deliberately cultivating plants whose glucosinolate content and composition are tailored to the health of humans.” One such plant might be broccoli, optimized to combat the stomach bacterium Helicobacter.

How the results were attained

As the object of their analysis, the international research team used the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Scientists know all there is to know about the genetic material of this model plant; it is also a “little sister” of cabbage, mustard, and rapeseed – it too contains glucosinolates and their transporters.

How did the scientists proceed? First of all, they applied a cellular biological approach. Using eggs from the South African clawed frog as a “test tube”, they conducted an assay to identify the genes needed to import and accumulate glucosinolates. In the end, the Danish team attributed this to two genes.

It was now the turn of the transporter specialists from Würzburg with their biophysical research methods – Professor Dietmar Geiger, in particular. They shed light on the mechanism that is used by these nanomachines sitting in the cell membrane to draw energy and transport the glucosinolates.

In the meantime, Barbara Ann Halkier from Copenhagen had isolated an Arabidopsis mutant in which neither transporter works: the plant had no glucosinolates whatsoever in its seeds. This proved that the researchers had indeed deciphered the genetic code and the function of the glucosinolate transporters that are so important to the survival of plants containing mustard oil.

The international research team

The team led by Professor Barbara Ann Halkier at the University of Copenhagen comprises experts in the field of glucosinolate metabolism. Professor Rainer Hedrich and Professor Dietmar Geiger from Würzburg are specialists in transport proteins in plants. The final member of this group of experts is former Würzburg plant scientist Ingo Dreyer, who is now a professor at the University of Madrid.

“NRT/PTR transporters essential for allocation of glucosinolate defense compounds to seeds”, Hussam Hassan Nour-Eldin, Tonni Grube Andersen, Meike Burow, Svend Roesen Madsen, Morten Egevang Jørgensen, Carl Erik Olsen, Ingo Dreyer, Rainer Hedrich, Dietmar Geiger, and Barbara Ann Halkier, Nature (2012), published online 05 august, DOI: 10.1038/nature11285

Contact

Prof. Dr. Rainer Hedrich, Department of Botany I (Molecular Plant Physiology and Biophysics) at the University of Würzburg, T +49 (0)931 31-86100, hedrich@botanik.uni-wuerzburg.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-wuerzburg.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…