Battle between the placenta and uterus could help explain preeclampsia

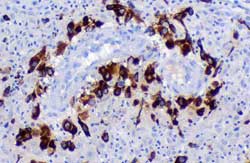

Invasive trophoblast (brown colored cells) surround and invade maternal cells. Credit: Harvey Kliman, Yale University<br>

The fetus must be big enough to thrive, yet small enough to pass through the birth canal. In a new study, Yale researchers describe the mechanism that keeps these conflicting goals in balance.

The findings are published in the October 11, 2011 online issue of Reproductive Sciences.

The battle is waged between the mother's uterus and the baby's placenta, which is made up of cells called trophoblasts that are controlled by the father. In the study, led by Harvey J. Kliman, M.D., research scientist in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences at Yale School of Medicine, researchers observed how the placenta tricks the mother so she doesn't attack the trophoblasts that are trying to increase the flow of her blood into the placenta. If this placental deception doesn't work the mother may develop preeclampsia, a condition that results in high blood pressure and protein in the mother's urine. The only known cure for preeclampsia is delivery of the baby.

The placenta's job is to get nutrients from the mother during pregnancy. Kliman explained that in a normal pregnancy, specialized invasive trophoblasts leave the placenta and invade the mother's tissues to attack and destroy the walls of her blood vessels. This allows the most blood possible to enter the placenta, resulting in a big baby.

But the mother's own “soldiers,” called lymphocytes, are constantly looking to destroy the invasive trophoblast cells. The placenta in turn appears to trick the mother by creating a diversion to occupy her lymphocytes.

The placenta creates this diversion by secreting a protein called placental protein 13 (PP13), also known as galectin 13, into the mother's blood where it travels through her veins into the uterus below the placenta. There the PP13 leaves the veins where it triggers the mother's immune system to react and attack. The entire area around these veins becomes a mass of inflammation and dead cells, called necrosis.

“We realized that these zones of necrosis are likely occupying the mother's soldiers while the invasive trophoblasts sneak into her arteries, leading to more blood flow to the placenta and a bigger baby,” said Kliman. “We believe that maintaining this balance could be the key to a healthy pregnancy free from preeclampsia.”

Other authors on the study include Marei Sammar, Yael Grimpel, Stephanie Lynch, Kristin Milano, Elah Pick, Jacob Bejar, Ayala Arad, James Lee, Hamutal Meiri and Ron Gonen.

The study was funded by a research grant from the European Union (FP6-grant # 037244, project title Pregenesys), the Finland Israel R&D Fund grant #41256 (Eureka – 3808 RPT), and the Yale University Reproductive and Placental Research Unit.

Citation: Reproductive Sciences doi: 10.1177/1933719111424445 (October 2011)

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.yale.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…