Failing protection of Africa's national parks

These anecdotes have increasingly been supported by quantitative data showing that wildlife outside national parks and game reserves has declined precipitously over the last 15 years (e.g., Caro et al., 1998; Stoner et al., 2007a). But now a raft of studies are showing that we have moved beyond this to the next step: we are losing species from many of Africa’s national parks – IUCN’s top flight category of protection – and bastion of biodiversity conservation worldwide (Terborgh & Van Schaik, 2002).

Why is this news suddenly? There are two reasons – both methodological. First, long-term datasets are being mined using sophisticated statistical methods that control for a plethora of confounding variables. These include a 40-year time span of monthly transects conducted by park guards in six Ghanaian National Parks (Brashares, 2003), and decade long collections of aerial censuses flown over huge wildlife areas in Kenya and Tanzania (Ottichilo et al., 2000; Stoner et al., 2007b). Secondly, conservation biologists have become less shy of combining and juxtaposing different survey methods to trace a picture of population changes within a single reserve across considerable time frames (Ogutu & Owen-Smith, 2005; Scholte, Adam & Serge, 2007; Van Vliet et al., 2007). Such studies generally focus on antelopes that are relatively easy to count from the air, from a vehicle, on foot, or by means of droppings. Most are delicious to eat.

The causes of these declines are principally anthropogenic and ultimately the result of human population growth, coupled with demands for a higher standard of living. But the proximate factors seem to vary on a case by case basis. Many parks are subject to the ravaging impact of illegal hunters, often local, but sometimes attracted from far away. Examples include Katavi National Park in Tanzania (Stoner et al., 2007b), Ipassa Man and Biosphere Reserve in Gabon (Van Vliet et al., 2007), and Comoé National Park, Côte d’Ivoire (Fischer & Linsenmair, 2007). In West-Central Africa, this bushmeat hunting is often the most common factor pressing upon antelope populations (Fa et al., 2005). In the old days this was for local consumption, now it includes tables in far off cities that, incredibly, extend to London and Paris.

Then there are reserves in which human encroachment, triggered by a galloping local demography or immigration (Scholte, 2003), is the driving force, with livestock infringing reserve boundaries (e.g., Stephens et al., 2001) or people moving into the reserves to farm (e.g., Lejju, 2004). Currently, there is a high profile debate going on in Uganda between sugar growers who want to grow their product in Mabira Forest Reserve 50 kms from Kampala and local conservationists who want to protect endemic bird species there (http://www.voanews.com/english/2007-06-08-voa53.cfm); five people have died in demonstrations.

Finally, in reserves too small to harbour wildlife populations year-round, multiple factors, natural and anthropogenic, operate in concert to diminish antelope populations. For instance, the crash in herbivores ranging from buffalo Syncerus caffer to giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis to wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus in the Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya results from a constellation of drought, poaching and increased wheat farm acreage in surrounding areas (Ottichilo et al., 2000).

There seem just a handful of exceptions to these anthropogenically driven declines. In the well-resourced Kruger National Park in South Africa downward trends of herbivore populations can be attributed unequivocally to nonhuman factors, namely dry season rainfall (Ogutu & Owen-Smith, 2005). And some species are even increasing, such as elephants Loxodonta africana faring relatively well inside and outside Eastern and Southern African reserves (Blanc et al., 2007). Arguably Africa’s premier flagship species, elephants receive public attention and attract resources for patrolling and management. But contrary to antelopes, elephants are targeted for bush meat only in Central Africa, while elsewhere the present ivory ban gives them some respite after decades of persecution.

We suspect that the documented herbivore population declines represent only the tip of the iceberg. Antelope populations have generally been poorly surveyed, and with the notable exceptions of the African Journal of Ecology articles quoted here, have failed to present quantitative information. More records must be tapped to quantify wildlife trends, especially in Western, Central and North-eastern Africa, but the new data confirm concerns raised by an earlier, qualitative, continent-wide antelope population assessment (East, 1999).

So what can we do to stop a pervasive diminution of antelope populations across the continent? There is no easy solution. Certainly, conservation biologists have identified a number of factors that promote bush meat consumption including opening up the forest to loggers (Robinson, Redford & Bennett, 1999); difficulties in obtaining other sources of animal protein (Brashares et al., 2004); and increasing standards of living driving demand for wild animals (East et al., 2005). But it is difficult, and in some cases immoral, to try to stop changes occurring at national and sometimes international scales. The old idea of setting aside large tracts of land in remote areas far from human populations is still a viable option in some parts of the continent (Mittermeier et al., 2003), one recently advocated for the extraordinary rediscovery of herbivore migrations in southern Sudan (http://www.wcs.org/353624/wcs_southernsudan). But it is a conservation approach increasingly outmoded by land-use change, demographics and policy reform. And, yes, beefed up infrastructure, increased patrols, vehicles, and incentives for park guards, in tandem with community outreach programs, will go some way to stop poaching; whereas internal and external opposition to land greedy development schemes may halt encroachment. What the new data show, however, is even relatively well-organized protected areas cannot be relied on as long-lasting conservation tools, at least for antelopes and their predators. In the final analysis, we may have to get used to faunal relaxation in Africa’s network of famous reserves (Soule, Wilcox & Holtby, 1979; Pullan, 1983) leaving a continent containing isolated pockets of large mammal diversity living at low population sizes. Just like Europe.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Ecology, The Environment and Conservation

This complex theme deals primarily with interactions between organisms and the environmental factors that impact them, but to a greater extent between individual inanimate environmental factors.

innovations-report offers informative reports and articles on topics such as climate protection, landscape conservation, ecological systems, wildlife and nature parks and ecosystem efficiency and balance.

Newest articles

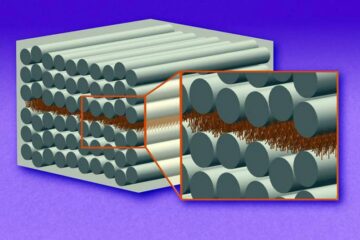

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…

Trash to treasure

Researchers turn metal waste into catalyst for hydrogen. Scientists have found a way to transform metal waste into a highly efficient catalyst to make hydrogen from water, a discovery that…

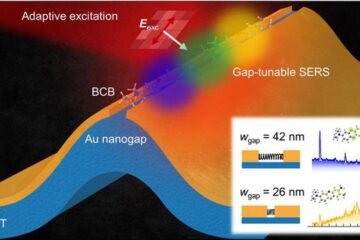

Real-time detection of infectious disease viruses

… by searching for molecular fingerprinting. A research team consisting of Professor Kyoung-Duck Park and Taeyoung Moon and Huitae Joo, PhD candidates, from the Department of Physics at Pohang University…