Unexpected information about Earth's climate history from Yellow River sediment

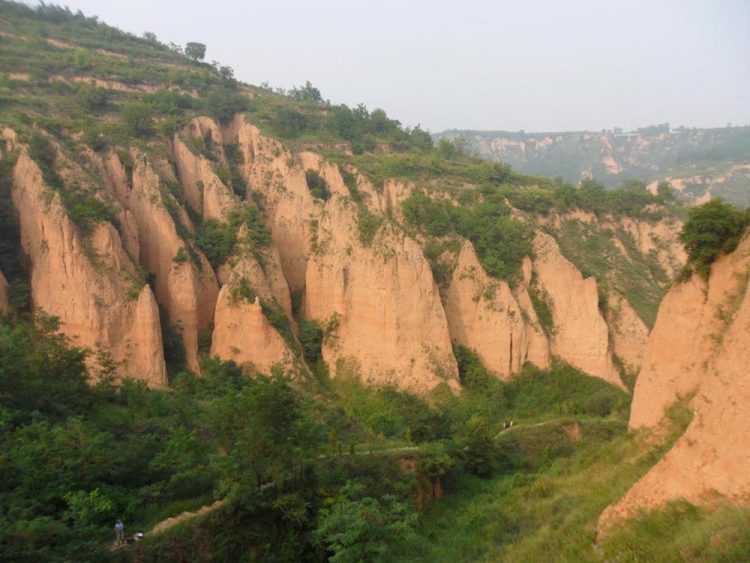

These are thick loess deposits on the Chinese Loess Plateau showing changing Ice Age climate. Visible dark bands are fossil soils from warm intervals and lighter intervals show enhanced dustiness during full ice age conditions Credit: Thoams Stevens

To reconstruct how the global climate and topography of the Earth's surface have developed over millions of years, deposits of eroded land sediment transported by rivers to ocean depths are often used. This process is assumed to have been rapid and, by the same token, not to have resulted in any major storages of this sediment as large deposits along the way.

However, knowledge gaps and contradictory data in research to date are impeding an understanding of climate and landscape history. In an attempt to fill the gaps and reconcile the contradictions, the researchers have been investigating present-day and ancient sediment deposits in the world's most sediment-rich river: the Yellow River in China.

The researchers, from Uppsala University (led by Dr. Thomas Stevens) and Lanzhou University (led by Dr. Junsheng Nie), China, analysed Yellow River sediment from source to sink and determined its mineral composition. They also determined the age of mineral grains of zircon, a very hard silicate mineral that is highly resistant to weathering.

Zircon ages serve as a unique fingerprint that yields information about the sources of these sediment residues from mountain chains, according to Thomas Stevens of Uppsala University's Department of Earth Sciences, one of the principal authors of the study.

The Yellow River is believed to gain most of its sediment from wind-blown mineral dust deposits called loess, concentrated on the Chinese Loess Plateau. This plateau is the largest and one of the most important past climate archives on land, and also records past atmospheric dust activity: a major driver of climate change.

The scientists found that the composition of sediment from the Yellow River underwent radical change after passing the Chinese Loess Plateau. Contrary to their expectations, however, the windborne loess was not the main source of the sediment. Instead, they found that the Loess Plateau acts as a sink for Yellow River material eroded from the uplifting Tibetan plateau.

This finding completely changes our understanding of the origin of the Chinese Loess Plateau. It also demonstrates large scale sediment storage on land, which explains the previously contradictory findings in this area.

'Our results suggest that a major change in the monsoon around 3.6 million years ago caused the onset of Yellow River drainage, accelerated erosion of the Tibetan plateau and drove loess deposition,' Thomas Stevens writes.

Weathering of this eroded material also constitutes a further mechanism that may explain the reduced levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide at the beginning of the Ice Age. The researchers' next step will be to compare terrestrial and marine records of erosion to gauge how far sediment storage on land has impacted the marine record.

'Only then will we be able to assess the true rates of erosion and its effect on atmospheric CO2 and thus the climate in geologic time,' says Stevens.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…