Meteorites offer glimpse of the early Earth, say Purdue scientists

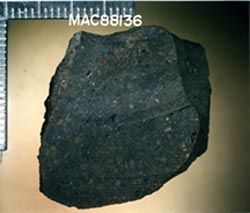

Purdue University’s Michael E. Lipschutz analyzed enstatite chondrite meteorites in a recent study of the materials near Earth at the dawn of the solar system about 4.5 billion years ago. Data from the study may offer clues into the conditions under which the Earth formed, evidence of which no longer exists in terrestrial stone. (NASA photo/ID number S91-41199)

Important clues to the environment in which the early Earth formed may be emerging from Purdue University scientists’ recent study of a particular class of meteorites.

By examining the chemistry of 29 chunks of rock that formed billions of years ago, probably in close proximity to our planet, two Purdue researchers, Michael E. Lipschutz and Ming-Sheng Wang, have clarified our understanding of the conditions present in the vicinity of the ancient Earth’s orbit. Because direct evidence for these conditions is lacking in terrestrial samples, the scientists believe that the composition of these so-called enstatite chondrite (EC) meteorites could offer a window into the planet’s distant past.

“What happened to these rocks most likely happened to the Earth in its early stages – with one great exception,” said Lipschutz, a professor of chemistry in Purdue’s College of Science. “Shortly after the early Earth formed, an object the size of Mars smashed into it, and the heat from the cataclysm irrevocably altered the geochemical makeup of our entire planet. These EC meteorites, however, are likely formed of matter similar to that which formed the early Earth, but they were not involved in this great collision and so were not chemically altered. They might be the last remaining pristine bits of the material that became the planet beneath our feet.”

The research appears in today’s (Sept. 27) edition of a new journal, Environmental Chemistry, which solicited the paper. Lipschutz said the journal’s editorial board includes F. Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina, who received the Nobel prize for their discovery that Earth’s protective ozone layer was threatened by human activity.

Lipschutz and Wang initially set out to increase our knowledge of EC meteorites, one of many different meteorite classes. Meteorites come from many different parts of the solar system, and a scientist can link one with its parent object by determining the different isotopes of oxygen in a meteorite’s minerals. Chunks of the moon, the Earth and EC meteorites, for example, have very similar isotopic “signatures,” quite different from those of Mars and other objects formed in the asteroid belt. The variations occurred because different materials condensed in different regions of the disk of gas and dust that formed the sun and planets.

Bits of these materials orbit the sun, occasionally falling to earth as meteorites. But there is one place on our planet that meteorites accumulate and are preserved in a pristine fashion – the ice sheet of Antarctica.

“Over the millennia, many thousands of meteorites have struck the Antarctic ice sheet, which both preserves them and slowly concentrates them near mountains sticking through the ice, much as ocean waves wash pebbles to the shore,” said Lipschutz. “These stones have come from many different parts of the solar system and have given us a better picture of the overall properties of their parent objects.”

By examining their mineralogy, scientists have determined that about 200 of these Antarctic stones are EC meteorites that formed from the same local batch of material as the Earth did more than 4.5 billion years ago. But there is additional information that the chemistry of these ECs can offer on the temperatures at which they formed. To obtain this information, however, required Lipschutz to analyze chemicals in the meteorites called volatiles – rare elements such as indium, thallium and cadmium.

“Volatiles in meteorites can give unique information on their temperature histories, but only 14 of them had ever been analyzed for these elements,” Lipschutz said. “Naturally, we want to know the story behind the formation of objects in our own neighborhood, so we set out to increase that number.”

In this study, the researchers gathered samples taken from another 15 EC meteorites that had, for the most part, landed in Antarctica tens of thousands of years ago. Using a unique method involving bombardment of the samples with neutrons, chemically separating the radioactive species and counting them, the researchers were able to determine the amounts of 15 volatiles that together offered clues to each rock’s heating history.

“Volatiles can act like thermometers,” Lipschutz said. “They can tell you whether the temperature was high or low when the rock formed. We tested two different kinds of ECs, and the oldest, most primitive examples of each kind had very similar volatile contents – which means their temperature at formation was similar. These rocks have essentially recorded the temperature at which the early Earth formed, and we now know that this was much lower than 500 degrees Celsius.”

The two different kinds of EC meteorites, known as ELs and EHs, were found in the Purdue study to have condensed at low temperatures like the Earth. However, the two groups are controversial because scientists have not been able to agree on whether they originated from a single parent object or two different ones. Unfortunately, Lipschutz said, the data from the 29 ECs they analyzed were insufficient to settle the issue.

“There are still quite a few unanswered questions about the earliest periods of the Earth’s history, and this study only provides one piece of the puzzle,” he said. “But aspects of this study also show that ECs differ substantially from other meteorite types that came from much farther out in the disk, in the region of the asteroid belt.”

For Lipschutz, who had an asteroid named for him on his 50th birthday in honor of his many studies of meteorites, their parent bodies and the early history of the solar system, deeper answers may lie farther away than Antarctica.

“If we understand how our solar system formed, we might be better able to understand the processes at work in other solar systems, which we are just beginning to discover,” he said. “Probing the asteroid belt could give us clues to these processes.”

This research was funded in part by NASA.

Writer: , (765) 494-2081, cboutin@purdue.edu

Source: Michael E. Lipschutz, (765) 494-5326, rnaapunl@purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.purdue.eduAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…