Internal waves appear to have the muscle to pump up mid-lats

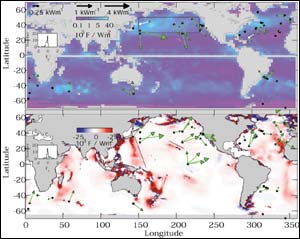

Maps, the first of their kind, show energy of internal waves carried away from where they originated. The larger and longer the arrows (vectors) the more energy is being carried away from where the waves originated. The upper map shows that, in general, internal waves generated by storms move through the ocean depths toward the mid-latitudes. The lower maps shows energy moving directly away from places where tidal forces have created internal waves.Graphic credit required: University of Washington/Nature <br>

When internal waves up to 300 feet first form they cause a mighty churning of ocean waters – something invisible to and unfelt by anyone at the surface.

Now in a novel use of mooring data, some of it three decades old, a University of Washington researcher has calculated just how much punch these waves appear to carry as they travel, or propagate, thousands of miles from where they originate.

It’s energy that appears to be crucial to the conveyor-belt-like circulation wherein millions of cubic meters of icy-cold water sink each second at high latitudes and are driven to upwell at lower latitudes. Without such upwelling, global ocean circulation would stall, causing the entire ocean to fill with cold water. Further, nutrients that have drifted down to the ocean depths would remain in the deep instead of being carried back to surface waters for use by plankton, the tiny plants and animals on which all other marine life depend and which greatly affect how much carbon dioxide is absorbed and released by the oceans.

Internal waves are just like waves one sees breaking on beaches except they occur completely below the surface. For the most energetic such waves, which get started either during stormy weather or when tides pull water across especially rough places on the seafloor, up to 50 percent of their original energy can be carried far away as the waves undulate through the ocean depths, according to Matthew Alford, an oceanographer with the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory.

That’s important because climate modelers need to know all the key factors that affect ocean mixing that occurs at mid-latitudes. Previous measurements and calculations by Alford, and by National Aeronautics and Space Administration and Oregon State University scientists, show that internal waves have the 2 trillion watts that would account for such ocean mixing.

Alford provides the first glimpse of how much of that energy actually makes it very far from where the waves originate.

“The fluxes . . . are large enough to transport, across ocean basins, globally significant amounts of energy available for mixing,” Alford wrote in the journal Nature last month. “Global mapping of their fluxes is an important step in determining how and where internal-wave mixing is accomplished.”

Alford, an Office of Naval Research Young Investigator, combed historical data from more than 1,000 moorings – some used for projects as far back as 1973. Sixty had instruments at the right depths and collected data for long enough, at least a winter, for Alford’s purposes. Moorings provide fair coverage of ocean waters in the North Atlantic and Pacific but very poor coverage in low latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, he says, something that could be considerably improved by deploying several well-placed moorings in the future.

He found that the kind of internal waves caused by tidal forces pulling water across underwater ridges, shoals, channels and other rough places on the seafloor, for example around the Hawaiian Islands, carry 30 percent to 50 percent of their energy directly away from their sources, a process that goes on year-round.

A second type of internal waves, one caused by sudden wind events and storms, appear to carry at least 15 percent to 20 percent of the energy input from where they originate, mainly during the stormy months of winter, and that energy is usually directed toward mid-latitudes areas. Alford says the focus in recent years has been on the importance of internal waves generated by internal tides, whereas his work suggests that internal waves generated by winds are just as significant.

###

For more information: Alford, 206-221-3257, malford@apl.washington.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.washington.edu/All latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…