Discovery may help protect crops from stressors

Scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have discovered a key genetic switch by which plants control their response to ethylene gas, a natural plant hormone best known for its ability to ripen fruit, but which, under stress conditions, can cause wilted leaves, premature aging and spoilage from over-ripening.

The findings, published August 30 in Science magazine, may hold the key to manipulating plants' ethylene on/off switch, allowing them to balance between drought resistance and growth and, therefore, decrease crop losses from drought conditions.

“In different stress conditions—-flooding, drought, chilling, wounding or pathogen attack—-ethylene tells plants to make adjustments to these adverse changes,” says senior study author Joseph Ecker, a professor in Salk's Plant Biology Laboratory and Howard Hughes Medical Institute-Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation investigator. “Our study discovered a key step in how plants 'smell' ethylene gas, which may lead to better ways to control these processes in crop plants.”

Plants sense—-or smell—-ethylene, which triggers a cascade of events in their cells. Ethylene sensors in the cells send a signal to the nucleus, the cells' central DNA-containing compartment, which initiates genetic programs so the plant can make changes according to the conditions it faces. Scientists, including Ecker and his team, have identified the functions of a number of key regulators in the ethylene signaling pathway, including the protein EIN2 (ethylene insensitive 2).

The EIN2 protein is located in the endoplasmic reticulum, the part of the cell that facilitates the transport of proteins within the cell, and plays an essential role in ethylene signaling. The protein's function, however, remains enigmatic. Through a variety of sophisticated tests, Ecker's team uncovered a mechanism by which EIN2 protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum and movement of signaling molecules into the nucleus are required to activate the ethylene response.

Understanding the mechanism may lead to new methods to help plants thrive in tough conditions. Stress conditions trigger various negative responses in plants, including wilted and rolled leaves, premature leaf senescence (aging), reduced photosynthetic efficiency, loss of chlorophyll, poor pollination, and flower, fruit and seed loss.

The most severe drought in 25 years is impacting crops across the United States, with the potential to wipe out farmers' incomes and raise food prices. Plant researchers are studying stress conditions in order to improve crop production, which has become more urgent as farmers around the world face climate issues such as drought and extreme temperatures. Curbing crops' susceptibility to certain stressors could allow for higher yields during droughts and possibly allow drier climates to support profitable crops and feed the world's growing population.

“Growers can opt to spray their plants with an ethylene inhibitor,” says Hong Qiao, a postdoctoral researcher in Ecker's laboratory and first author of the paper. “This blocks the plant's ethylene receptors from smelling ethylene, which has an effect on growth. Without the ethylene response pathway, a tomato would never ripen. Too much ethylene, and the tomato over-ripens. Therefore, basic knowledge of the precise mechanism by which plants control the response to ethylene gas will lead to better ways to control these processes in crop plants.”

Other researches on the study were Shao-shan Carol Huang, Robert J. Schmitz and Mark A. Urich, from the Salk Institute; and Zhouxin Shen and Steven P. Briggs of the University of California, San Diego.

The work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines.

Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.salk.eduAll latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

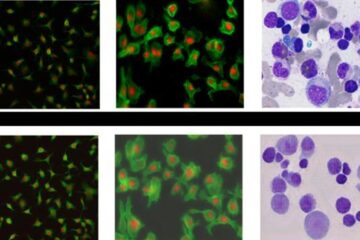

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…