Appearance not always enough to identify species

“If you can’t recognise a species by looking at it, this can have serious consequences,” says Emma Vodoti from the Department of Zoology at the University of Gothenburg.

“For example, there is a species of leech that is widely used in medical studies, and it was discovered recently that sometimes a leech was being used that looks the same but has a different genetic make-up. This naturally has an effect on the results of the studies conducted. All work based on having to be able to identify species may have to change.”

350 years after Linnaeus created his system for organising and categorising species of plants and animals, the system is being pulled apart. Newly discovered organisms are still categorised and named in line with his system, but there is a big difference between species described before and after the discovery of DNA. Until the 1980s, scientists had to rely entirely on appearance, anatomy and other characteristics, such as a bird’s song. Since then, genetic patterns have also been taken into account when identifying new species.

“Ironically, these genetic studies have erased many of the established boundaries between species and even disproved the existence of previously described species that have turned out not to be related. Attempts have been made to establish universal boundaries between species by quantifying how much DNA needs to be different between two organisms in order for them to be viewed as separate species, but this doesn’t always work.”

In her thesis, Vodoti looks at the practical problems with species identification today, after having studied the relationship between the genetic relatedness and the appearance and geographical distribution of various sea creatures. The common horse mussel Modiolus modiolus found in the Atlantic and on the west coast of Sweden turns out to be totally different genetically from the one found on the Pacific coast of the USA, despite looking identical.

Nemertean worms may have similarities in appearance but turn out to consist of a hotchpotch of different species, more or less independent of looks. Nemerteans include worms just a few millimetres in length to one of the world’s longest creatures, Lineus longissimus, which can grow up to 15 metres.

“It’s probably impossible to find a universal way of defining, identifying and delimiting species,” says Vodoti. “My thesis shows that there is a need for individual assessment on a case-by-case basis when identifying species, taking account of both appearance and genes.”

Contact:

Emma Vodoti

0730-930639

iktis@hotmail.com

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

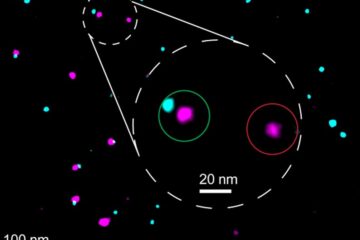

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…