Quantum cats are hard to see

International team of researchers explain the difficulty of detecting quantum effects

Are there parallel universes? And how will we know? This is one of many fascinations people hold about quantum physics. Researchers from the universities of Calgary and Waterloo in Canada and the University of Geneva in Switzerland have published a paper this week in Physical Review Letters explaining why we don't usually see the physical effects of quantum mechanics.

“Quantum physics works fantastically well on small scales but when it comes to larger scales, it is nearly impossible to count photons very well. We have demonstrated that this makes it hard to see these effects in our daily life,” says Dr. Christoph Simon, who teaches in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Calgary and is one of the lead authors of the paper entitled: Coarse-graining makes it hard to see micro-macro entanglement.

It's well known that quantum systems are fragile. When a photon interacts with its environment, even just a tiny bit, the superposition is destroyed. Superposition is a fundamental principle of quantum physics that says that systems can exist in all their possible states simultaneously. But when measured, only the result of one of the states is given.

This effect is known as decoherence, and it has been studied intensively over the last few decades. The idea of decoherence as a thought experiment was raised by Erwin Schrödinger, one of the founding fathers of quantum physics, in his famous cat paradox: a cat in a box can be both dead and alive at the same time.

But, according to the authors of this study, it turns out that decoherence is not the only reason why quantum effects are hard to see. Seeing quantum effects requires extremely precise measurements. Simon and his team studied a concrete example for such a “cat” by using a particular quantum state involving a large number of photons.

“We show that in order to see the quantum nature of this state, one has to be able to count the number of photons in it perfectly,” says Simon. “This becomes more and more difficult as the total number of photons is increased. Distinguishing one photon from two photons is within reach of current technology, but distinguishing a million photons from a million plus one is not.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ucalgary.caAll latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

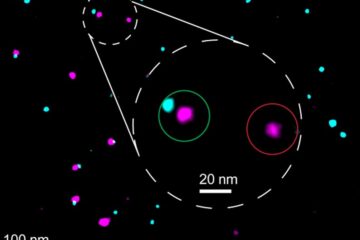

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…