Dependency can be an evolutionary advantage

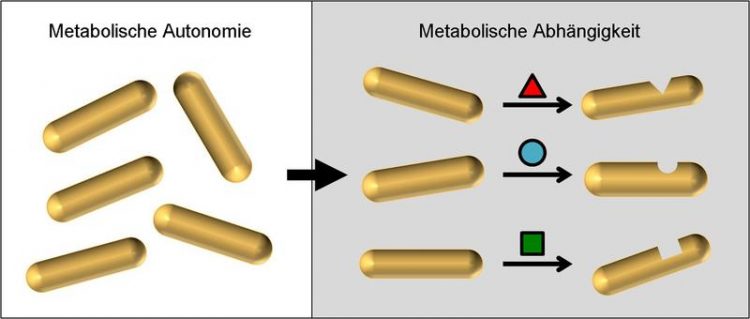

Bacterial populations diversify into two genetically distinct populations: One retains biosynthetic capabilities and the other loses these functions. The latter thus becomes metabolically dependent. Glen D’Souza, Christian Kost / Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

It has been known for quite some time that genetically modified bacteria, which have lost their ability to produce certain amino acids and retrieve these nutrients from their environment grow better than bacteria, which produce all nutrients themselves (see press release Division of Labor in the Test Tube, December 2, 2013).

This led Christian Kost, leader of the study and now professor at the University of Osnabrück, to inquire whether natural selection would favor the loss of abilities, thus making bacteria more dependent on their environment. To find out, Kost and his PhD student Glen D’Souza cultivated the gut bacterium Escherichia coli bacteria for several generations under optimal nutritious conditions. The culture was regularly transferred to a fresh nutrient solution, and during some of these transfers, a sample was taken to examine the bacterial capabilities and genes.

The results confirmed the assumption: A fraction of bacteria which had originally been autonomous lost their ability to produce metabolites, such as amino acids; they had become dependent on their environment which was enriched with these nutrients. “To our surprise, we found similar results when no nutrients had been added to the culture medium,” explained Glen D’Souza, the first author of the study. “The bacteria were divided into two groups: One group was still independent, whereas the other group had become dependent on these autonomous bacteria, which were still producing nutrients by themselves.”

A similar loss of traits has been observed not only in bacteria, but also in other groups of organisms. Many animals, including humans, are not able to produce vitamins themselves – they depend on their food or on vitamin-producing bacteria in their gut. Many pathogens need substances produced by their hosts in order to proliferate. Until now, it has been unclear why organisms would give up their autonomy and become dependent on others. This study now shows that the loss of capabilities may be evolutionarily advantageous and thus drive adaptation.

“There were further results we had not expected at all: When we studied the genome of the dependent bacteria, we found mutation not only in genes that are directly involved in the biosynthesis of amino acids, but also in genes, which regulate proteins that are involved in activating or inhibiting metabolic processes,” Christian Kost reports. This means that the adaptation of a bacterial population can be achieved in different ways. In the current study, this adaptation occurred only in one direction:

One group of bacteria became dependent on the other. However, the researchers are convinced that a longer testing period would have eventually resulted in mutual and more complex dependencies. Therefore, they plan to extend the duration of their experiment. Natural selection depends not only on the genetic endowment of a population, but also on its size. Depending on their lifestyle, natural bacterial populations differ considerably in size. Hence, the scientists want to find out how the size of bacterial populations affects the development of dependencies and the changes in the bacterial genomes.

A major problem in biological research is that most bacteria cannot be cultured under laboratory conditions. The results of the new study may explain why this is the case: Bacterial populations rapidly evolve metabolic dependencies on their environment by loosing the corresponding biosynthetic genes. Metagenomic analyses of environmental samples, which include the ecological interactions of microbial communities with their natural environments, may help solve this problem.

The experimental results are also relevant in more applied contexts: After all, bacterial communities play an important role in the health of plants, animals, and humans. Metabolic cooperation – that is, the question of how bacteria contribute to the exchange of metabolites – could become a decisive factor when bacterial communities are selected for application in agriculture or health care in order to support either growth or the defense against pathogens. [KG/AO]

Original Publication:

D’Souza, G., Kost, C. (2016). Experimental evolution of metabolic dependency in bacteria. PLOS Genetics. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006364

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006364

Further Information:

Prof. Dr. Christian Kost, Abteilung Ökologie, Fachbereich Biologie, Universität Osnabrück, Barbarastraße 13, 49076 Osnabrück, Tel: Tel. +49 541 969-2853, E-Mail christiankost@gmail.com

Contact and Media Requests:

Angela Overmeyer M.A., Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Str. 8, 07743 Jena, +49 3641 57-2110, E-Mail overmeyer@ice.mpg.de

Download high-resolution images via

http://www.ice.mpg.de/ext/downloads2016.html

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…