Hurricanes at the Equator: "Impossible Perfect Storm" Observed

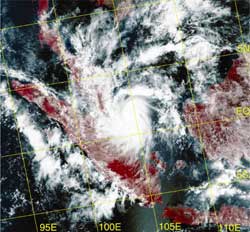

The Modis satellite image shows Typhoon Vamei at 1.5 degrees North near Singapore on December 27, 2001, with circulation on both sides of the equator. The land areas are the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra to the west of the typhoon, and Borneo to the east. <br>Satellite Image Credit: CRISP/National University of Singapore <br>

Hurricanes cannot form near the equator, or so meteorology textbooks maintain. But a storm named Typhoon Vamei upended scientists’ thinking when it swirled above the equator in the South China Sea near Singapore on December 27, 2001. It formed so close to the equator that its winds howled in both hemispheres.

New research funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research reveals the unusual mechanism for the birth of such a storm.

Intense thunderstorms over expanses of warm ocean water roil the atmosphere. Earth’s rotation spins these storms through the Coriolis Effect, a deflection that results in storms whirling counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere.

The quiescent region for this force (much like the “eye” of a hurricane) is at the equator, so researchers once believed nascent storms in this region could not build the power to start spinning. Before Typhoon Vamei (hurricanes are called typhoons when they form over the Pacific Ocean), no hurricane in recorded history had formed within 200 miles of the equator.

“Typhoon Vamei happened because of two interacting systems, a weak circulation that formed over Borneo and drifted into the southern tip of the South China Sea and remained there, and a strong and persistent northeast wind surge that turned as it crossed the equator and created a large background rotation,” explained NSF-awardee C.P. Chang, a meteorologist at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. Chang collaborated with meteorologists C.H. Liu from the Chinese Culture University and H.C. Kuo from the National Taiwan University, both sponsored by Taiwan’s National Science Council.

“The mechanism we identified raises additional questions,” remarked Chang. “Both the wind surge and the Borneo thunderstorms are common features of the winter monsoon. Why was an equatorial cyclone not observed before?”

From analyses of weather model and satellite data, the researchers found that the land-sea terrain in the equatorial South China Sea, while necessary for strengthening and turning the cross-equatorial wind surge, also places a time constraint on the confluence of events that occurred in December of 2001. Nonetheless, Vamei still wreaked havoc: U.S. Navy ships were damaged by the typhoon, and the southern Malay Peninsula was flooded by storm surges from its 87-mile-per-hour winds.

“When something like this happens—intense background winds wrapping around a weak disturbance that lingers over warm ocean waters—and that vortex starts to spin with no help from Earth’s rotation, unlikely factors have come together,” said Chang. “What you have then is just about ’the perfect storm.’ The probability of a similar equatorial development is estimated to be once every 100 to 400 years, and it probably cannot happen outside the southern South China Sea.”

NSF Science Expert: Pam Stephens, pstephen@nsf.gov

NSF Principal Investigator: C. P. Chang, cpchang@nps.navy.mil

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nsf.gov/od/lpa/news/03/tip030512.htmAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…