Making adult language learning child’s play

A sophisticated new language learning method that uses technology to implement findings from neuroscience aims to be simplicity itself for adult learners.

Mobility within the European Union offers great prospects for both individuals and companies – but doing business in another country only makes sense if you can speak (or quickly learn) the local language. Unfortunately, recent statistics have shown that 51 per cent of EU citizens cannot speak a European language other than their mother tongue – a surprisingly low number given that over 90 per cent of Europeans learn a second language at school.

“The problem is that today’s typical approach to language learning is too intellectual,” explains Ralph Warnke, the coordinator of the IST programme-funded FLIC project behind the courses. Slavishly learning the grammar of a language along ‘la plume de ma tante’ lines does not enable us to speak it, as all too many of us can testify. “Based on our observation of how bilingual children learn languages, we decided to find an easier way for adults to pick up a second tongue,” says Warnke.

Warnke is Managing Director and President of MediTECH, a German company that devised Brain-Boy®, a kind of portable game computer that is a highly effective, technology-enabled way of improving the language abilities of dyslexic children, by training them in eight basic language functions such as pitch discrimination and spatial hearing. “For dyslexics, their own language is like a foreign language,” explains Warnke. “So that got me thinking, why shouldn’t the same approach work with adult language learners?”

FLIC uses a feedback system, equipping learners with a headset (earphones) and microphone, plus a black box (or programme, in the case of the home version), which mixes the sound. When learners begin a FLIC course, they start by reading text while listening to it being pronounced by a model voice in the earphones. Next, they mouth the text while listening to the words (“The brain is working although the voice is silent,” explains Warnke). Step three is actually speaking the words out loud.

Then – and this is the clever part – the system plays back the learner’s efforts in one ear, and the model voice in the other ear. “And it doesn’t stay in the same ear, but moves from ear to ear, so that inter-hemispheric contact is enhanced,” explains Warnke. “Both hemispheres are very important for language learning. The left hemisphere is involved in word recognition, it’s the word processor of the brain; but the right hemisphere rules prosody – a vital decoding process that uncovers non-explicit shades of meaning.”

Using the learner’s own voice aids learning, because research shows that we pay most attention to voices like our own. So, in the next stage, FLIC uses this fact by modifying the model voice, blending it with the learner’s voice, which has been divided into bands and analysed for speed, pitch, and so on using software developed by Stockholm’s KTH, one of the FLIC project’s partners. The resulting voice mimics the learner’s own, yet has the superior pronunciation of the model voice. “When learners hear this, they experience themselves speaking a foreign language much better than they expected,” says Warnke. “They are then happy to keep practising and speaking.”

An innovative use of voice techniques is also used to improve vocabulary retention. Learners hear a word in the target language in one ear, and its meaning in their own language in the other ear, simultaneously. “Again, the words and translations switch between the ears, and so the hemispheres,” says Warnke.

Learners listen and participate in dialogues, picking up the structure of the language by example, without ever having to endure a grammar lesson. “They absorb the rules naturally, which is exactly how small children learn languages,” says Warnke. “FLIC gives people an internal pattern of a language that they don’t get with other systems.”

After three years in development and testing, the FLIC trials are currently being evaluated by the University of Sheffield, UK, and full results are expected in May.

“The testing phase took place in five different sites in three countries: France, Germany and Italy,” explains Warnke. “Beginners, intermediate and advanced groups took courses of between 24 and 48 total hours, while control groups took conventional courses. Preliminary findings indicate that FLIC cuts language learning time by 50 per cent.” Acceptance of the method was high, among both students and teachers. So far, FLIC offers courses in English, German, and Italian, but other languages can easily be added.

Warnke hopes to commercialise the product in the near future, pointing out that its availability as both software and hardware make it suitable for individuals (home users) as well as groups (language schools).

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Science Education

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

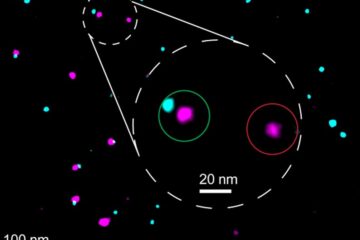

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…