Laser lights new path for homeland security

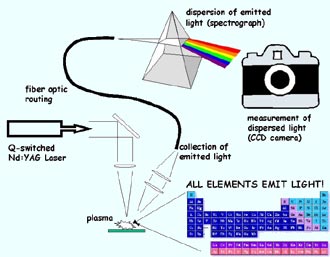

Schematic of a LIBS system <br>Courtesy of US Army Research Laboratory

Instant detection for chemicals, explosives, and biohazards

A little over a year after September 11, a laser technique is lighting a new path to homeland security. In recent Army laboratory research, this technique instantly detected and identified various explosives.

Preliminary results indicate that it can also tell the difference between several close relatives of anthrax.

Recent breakthroughs now let it detect any known substance, at least in theory. The laser technique-called LIBS, for laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy -is the subject of a meeting sponsored by the Optical Society of America in Orlando later this month.

“September 11 has heightened the need for much better sensors for detecting explosives, biological and chemical agents…and anything else that is harmful to anyone including the citizens of this country,” says researcher Andrzej Miziolek (pronounced miz-E-oh-lek) of the United States Army Research Laboratory. On September 25, Miziolek will chair a panel discussion on LIBS and homeland defense at the Orlando meeting.

ARMY RESEARCH DETECTS HAZARDOUS COMPOUNDS—IN AN INSTANT

A Florida company called Ocean Optics Inc. makes the state-of-the-art spectrometer the Army used in recent research. The LIBS laser zapped the target sample, such as contaminated soil, and “has the potential of detecting various explosives in a single shot,” says Miziolek.

In other preliminary research, Miziolek and colleagues used LIBS on three strains of bacteria, all closely related to the bacterium that causes anthrax. The laser light pulverized the bacteria spores into atoms and molecules. LIBS analyzed the mix so precisely, Miziolek says, that it detected at least 15 spectral differences among the three types of bacteria.

HE FUTURE OF LIBS

The Army’s still continuing research, but Miziolek and fellow LIBS researchers already have visions of the kinds of things that LIBS can do. They need to test LIBS much more and make it truly portable. But these practicalities have not stopped LIBS researchers from envisioning the possibilities for improving homeland security.

At subway stations and other high-traffic environments, a LIBS system could continuously monitor the air for signs of chemical or biological agents and alert officials if it finds a potentially hazardous substance. Combine LIBS systems with filters, Miziolek says, and you could detect an agent, then zap an electric charge on it, draw it towards a pair of electrodes, and capture and destroy the agent before it does any damage.

“There hasn’t been a lot of funding in developing LIBS so far”-Miziolek says, but he expects that September 11-and the promising research at the Army and elsewhere-are going to change this situation.

DETECTION FROM A DISTANCE

Researchers envision a LIBS wand that examines suspicious materials, such as a suspicious powder. Workers could fire the laser to analyze a target that’s hundreds of feet away. Or, designers could thread it through fiber optics to analyze concealed materials-a capability that would be helpful for monitoring hard-to-access areas.

INEXPENSIVE AND PORTABLE

What’s more, a LIBS system is fairly inexpensive-approximately $50,000 for a system that can detect a wide range of substances, and less than $20,000 for a LIBS system optimized for specific threats.

LIBS is also convenient. “The whole LIBS technique has great potential to be made portable,” according to Miziolek. It requires a laser “the size of a flashlight,” he says, and even the most powerful LIBS detectors are only a couple of shoeboxes in size.

HOTTER THAN PARTS OF THE SUN

A LIBS laser pulse heats a tiny portion of the sample to temperatures of up to 43,000 degrees Fahrenheit (approx 24,000 degrees Kelvin), hotter than some parts of the sun. The laser pulse-lasting just nanoseconds, or billionths of a second–zaps a specimen, such as an unknown powder, a test tube containing suspicious bacteria, or even a spot of air.

The extreme heat breaks matter into plasma-a collection of atoms and ions (positively charged atoms and molecules) and negatively charged electrons. After about a millionth of a second, the ions and electrons combine to form atoms and molecules again. But now these atoms and molecules are highly energized. To shed this energy, each kind of atom or molecule radiates its “elemental fingerprint”-a unique spectrum of light that reveals its identity.

“For every element,” Miziolek says, “we know what colors of light an atom will emit.”

DETECTORS CAN IDENTIFY ANYTHING

LIBS can identify any known substance, in principle, from what’s in a volcanic rock to a particular strain of bacteria to an unknown explosive. “The recent laboratory results have been exciting and encouraging, but have yet to be proven in the field. However, with the recent significant advances in the hardware and software, the goal of field-portable instruments is right around the corner, say in a year’s time-frame” says Miziolek.

Once LIBS detects the types and quantities of chemicals, it consults chemical profiles of known substances, like TNT. If the instrument records a certain proportion of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen, it can then check a computer database to see if this matches the exact proportion of elements in TNT-or any other substance in the database.

U.S. DEVELOPED IT, THEN FORGOT IT

LIBS has been around since the early 1980s, when researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory invented it for chemical analysis. However, LIBS didn’t really catch on in the US. Instead, other countries picked up on the technology. At a recent LIBS conference with 130 papers, Miziolek remembers, US research teams presented fewer than 15 papers.

“This is a technique that’s still quite new to the US,” Miziolek says. “But that’s about to change significantly because of September 11,” he says.

SAFETY AT HOME, EXPLORING MARS, KEEPING ATHLETES HONEST

Homeland security is not LIBS’ only use.

This winter, Olympics officials used LIBS to be sure bobsledders were using regulation metals in their bobsleds.

Contact:

Ben Stein

American Institute of Physics

301-209-3091

bstein@aip.org

Craig Smith

American Institute of Physics

301-209-3088

csmith@aip.org

Colleen Morrison

Optical Society of America

202-416-1437

cmorri@osa.org

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.osa.org/meetings/topicals/LIBS/All latest news from the category: Process Engineering

This special field revolves around processes for modifying material properties (milling, cooling), composition (filtration, distillation) and type (oxidation, hydration).

Valuable information is available on a broad range of technologies including material separation, laser processes, measuring techniques and robot engineering in addition to testing methods and coating and materials analysis processes.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…