Slow motion: antiprotons unravel atoms

Quantum mechanics makes it easy to describe hydrogen, the simplest atom, but bigger atoms are more complicated owing to interactions between their electrons. It is especially difficult to predict the dynamics of atomic reactions during a collision. Now a team including RIKEN researchers has shed more light on this problem by performing collision experiments with slow beams of particles called antiprotons (1).

The researchers, based at the CERN particle accelerator complex in Switzerland, bombarded helium atoms with antiprotons. There is particular demand to do this with very slow antiproton beams, because current theories may not be accurate for low-energy collisions.

“Ionization by an antiproton, a unique heavy negative particle, is in itself quite exotic,” explains RIKEN scientist Yasunori Yamazaki. “In addition to this, helium is one of the most important targets to study collision dynamics because it has two electrons with a strong correlation between them.”

At CERN, antiprotons are produced in a nuclear reaction which gives them very high energies measured in billions of electron volts. They are then collected in an AD (antiproton decelerator), cooled and decelerated, so that their energies are reduced to a few million electron volts.

Yamazaki and co-workers constructed a new ‘radio frequency quadrupole decelerator’ and a ‘multi-ring trap’ to reduce the antiproton energy further down to a fraction of an electron volt, before re-accelerating them to 3,000–25,000 electron volts. This corresponds to speeds around 6,000 meters per second—very slow in particle accelerator terms.

The researchers directed their beam of slow antiprotons onto a jet of helium and argon, and monitored the energies of ions created. Their results show that the new theoretical models of low energy reactions are working, as Yamazaki explains.

“The previous experimental data did not agree with any reasonable theories, so there were big discussions on whether we forgot to include some important effects,” he says. “The good news is that it looks like our understanding on the collision dynamics of a slow antiproton and helium atom is now within satisfactory levels.”

Yamazaki and co-workers plan to develop more sophisticated equipment in order to achieve even lower antiproton energies, and observe not only the ions created during collisions, but also the electrons ‘knocked off’ the atoms. At lower energies the antiproton may get trapped in an orbit of the target atom, creating an interesting ‘molecule’ called an antiprotonic atom. The data could even help scientists investigating the use of antiprotons in treating cancer.

Reference

1. Knudsen, H., Kristiansen, H.-P.E., Thomsen, H.D., Uggerhøj, U.I., Ichioka, T., Møller, S.P., Hunniford, C.A., McCullough, R.W., Charlton, M., Kuroda, Y., et al. Ionization of helium and argon by very slow antiproton impact. Physical Review Letters 101, 043201 (2008).

The corresponding author for this highlight is based at the RIKEN Atomic Physics Laboratory

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…

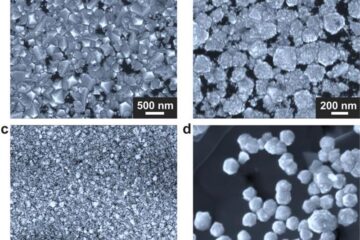

Making diamonds at ambient pressure

Scientists develop novel liquid metal alloy system to synthesize diamond under moderate conditions. Did you know that 99% of synthetic diamonds are currently produced using high-pressure and high-temperature (HPHT) methods?[2]…

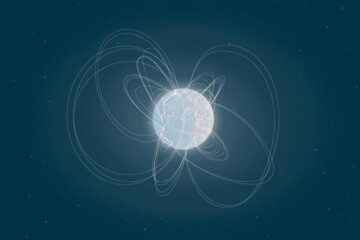

Eruption of mega-magnetic star lights up nearby galaxy

Thanks to ESA satellites, an international team including UNIGE researchers has detected a giant eruption coming from a magnetar, an extremely magnetic neutron star. While ESA’s satellite INTEGRAL was observing…