Globular star clusters: The survivors of a massacre 13 billion years ago

These globular clusters are almost as old as the universe itself and hold valuable information on how the first generations of stars and galaxies formed. Now a team of astronomers from Germany and the Netherlands have conducted a novel type of computer simulation that looked at how they were born – and they find that these giant clusters of stars are the only survivors of a 13 billion year-old massacre that destroyed many of their smaller siblings. The new work, led by Dr Diederik Kruijssen of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching appears in a paper in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Globular star clusters have a remarkable characteristic: the typical number of stars they contain appears to be about the same throughout the Universe. This is in contrast to much younger stellar clusters, which can contain almost any number of stars, from fewer than 100 to many thousands. The team of scientists proposes that this difference can be explained by the conditions under which globular clusters formed early on in the evolution of their host galaxies.

The researchers ran simulations of isolated and colliding galaxies, in which they included a model for the formation and destruction of stellar clusters. When galaxies collide, they often generate spectacular bursts of star formation (“starbursts”) and a wealth of bright, young stellar clusters of many different sizes. As a result it was always thought that the total number of star clusters increases during starbursts. But the Dutch-German team found the opposite result in their simulations.

While the very brightest and largest clusters were indeed capable of surviving the galaxy collision due to their own gravitational attraction, the numerous smaller clusters were effectively destroyed by the rapidly changing gravitational forces that typically occur during starbursts. After the starburst had ended, the researchers were surprised to see that only clusters with high numbers of stars had survived. These clusters had all the characteristics that should be expected for a young population of globular clusters, as they would have looked about 11 billion years ago.

Dr Kruijssen comments: “It is ironic to see that starbursts may produce many young stellar clusters, but at the same time also destroy the majority of them. This occurs not only in galaxy collisions, but should be expected in any starburst environment. In the early Universe, starbursts were commonplace – it therefore makes perfect sense that all globular clusters have approximately the same large number of stars. Their smaller brothers and sisters that didn’t contain as many stars were doomed to be destroyed.”

According to the simulations, most of the star clusters were destroyed shortly after their formation, when the galactic environment was still very hostile to the young clusters. After this episode ended, the surviving globular clusters have lived quietly until the present day.

The researchers have further suggestions to test their ideas. Dr Kruijssen continues: “In the nearby Universe, there are several examples of galaxies that have recently undergone large bursts of star formation. It should therefore be possible to see the rapid destruction of small stellar clusters in action. If this is indeed found by new observations, it will confirm our theory for the origin of globular clusters.”

The simulations suggest that most of a globular cluster’s traits were established when it formed. The fact that globular clusters are comparable everywhere then indicates that the environments in which they formed were very similar, regardless of the galaxy they currently reside in. In that case, Dr Kruijssen believes, they can be used as fossils to shed more light on the conditions in which the first stars and galaxies were born.

Original publication:

Kruijssen et al, “Formation versus destruction: the evolution of the star cluster population in galaxy mergers”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, in press http://arxiv.org/abs/1112.1065

Science Contact:

Dr Diederik Kruijssen

Max-Planck Institute for Astrophysics

Garching, Germany

Tel: +49 (0)89 30000 2241

E-mail: kruijssenmpa-garching.mpg.de

Media Contact:

Dr Robert Massey

Royal Astronomical Society

Tel: +44 (0)20 7734 3307 x214

Mob: +44 (0)794 124 8035

Email: rmras.org.uk

Dr Hannelore Hämmerle

Press officer

Max-Planck Institute for Astrophysics

Garching, Germany

Tel: +49 (0)89 30000 3980

E-mail: prmpa-garching.mpg.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

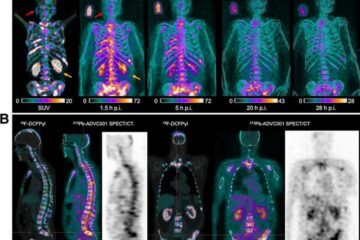

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…