Seeing the world differently

Wellcome Trust scientists have shown for the first time that exactly how we see our environment depends on the size of the visual part of our brain.

We are all familiar with the idea that our thoughts and emotions differ from one person to another, but most people assume that how we perceive the visual world is usually very similar from person to person. However, the primary visual cortex – the area at the back of the brain responsible for processing what we see in the world around us – is known to differ in size by up to three times from one individual to the next.

Now, researchers at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at UCL (University College London) have shown for the first time that the size of this area affects how we perceive our environment. Their study is published online today in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Dr D Samuel Schwarzkopf, Chen Song and Professor Geraint Rees showed a series of optical illusions to thirty healthy volunteers. These included the Ebbinghaus illusion, a well-known illusion in which two circles of the same size are each surrounded by circular 'petals'; one of the circles is surrounded by larger petals, the other by smaller petals. Most people will see the first circle as smaller than the second one

In a second optical illusion, the Ponzo illusion, the volunteers were shown two identically sized circles superimposed onto the image of a tunnel. In this illusion, the circle placed further back in the tunnel appears larger than that placed near the front.

By adapting these illusions, the researchers were able to show that individual volunteers saw the illusions differently. For example, some people saw a big (although illusory) difference in size between the two circles, but others barely saw any difference in apparent size.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers were also able to measure the surface area of the primary visual cortex in each volunteer. They found a great deal of variability in the size of this area. Surprisingly, there was a strong link between its size and the extent to which volunteers perceived the size illusion – the smaller the area, the more pronounced the visual illusion.

“Our work is the first to show that the size of part of a person's brain can predict how they perceive their visual environment,” explains Dr Schwarzkopf.

“Optical illusions mystify and inspire our imagination, but in truth they show us that how we see the world is not necessarily physically accurate, but rather depends a lot on our brains. Illusions such as the ones we used influence how big something looks; that is, they can trick us into believing that two identical objects have different sizes.

“We have shown that precisely how big something appears to you depends on the size of a brain area that is necessary for vision. How much your brain tricks you depends on how much 'real estate' your brain has put aside for visual processing.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.wellcome.ac.ukAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

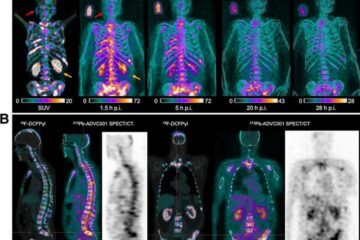

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…