Jefferson and Michigan Scientists Identify Gene Defect Behind Muscle-Wasting Disease

Insights gained from extensive studies in mice may someday lead to treatments for comparable neurodegenerative diseases in humans

Scientists at Jefferson Medical College and the University of Michigan have uncovered a gene defect responsible for a muscle-wasting, neurodegenerative disease in mice known as mnd2. Their results may provide insights into the molecular origins of other such diseases in humans, including Parkinson’s disease.

In an online report on October 8 in the journal Nature, the researchers, led by Emad Alnemri, Ph.D., at Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, and Miriam Meisler, Ph.D., at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, showed that a mutation in a single amino acid in the protein Omi/HtrA2 is enough to cause the neuromuscular disease. In mnd2 mice, the amino acid serine is changed to cysteine.

Michigan senior research associate Julie Jones, a member of Dr. Meisler’s research team, discovered the mnd2 mouse model, an inherited neurological disease, in 1990. mnd2 is characterized by an abnormal gait, muscle wasting and early death. To identify the guilty gene, Dr. Meisler’s laboratory used a technique called positional cloning, eventually narrowing the mutation to a small region containing six candidate genes on chromosome 6. To find the specific genetic defect, they determined the nucleotide sequence of these candidate genes and discovered that the mnd2 defect was caused by a “point” mutation in the Omi gene.

Dr. Alnemri had been studying the Omi/HtrA2 protease – an enzyme that cleaves proteins – and its role in programmed cell death. When he located the Omi gene on chromosome 2p13.1 – which happened to correspond to mouse chromosome 6, where the mnd2 locus is found – he suspected that a mutation in the Omi/HtrA2 gene could be behind the mnd2 disease. According to Dr. Alnemri, who is professor of microbiology and immunology at Jefferson Medical College and a member of Jefferson’s Kimmel Cancer Center, Omi/HtrA2 is present in the mitochondria, which generates energy in the cell. Omi regulates apoptosis, or programmed cell death, by binding and cleaving proteins that block the process. He and his co-workers at Jefferson characterized the mutation and discovered that it causes a loss of proteolytic activity of the protein, though the mutant protease can still bind to apoptosis-blocking proteins.

The Jefferson team performed additional tests on both normal and mutant mice cells, revealing that the cells from mutant mice were more sensitive to cellular stresses. They also discovered that mitochondria are defective in these cells as well. “The normal protease helps maintain normal mitochondrial function and is important for maintaining survival of cells in the nervous system,” says Dr. Alnemri.

The finding was surprising, says Dr. Meisler, a professor in the Department of Human Genetics at Michigan, because “Omi had not been thought to be involved in neurological disease. It appears to cause neuronal cell death by impairment of mitochondrial function.” “Interestingly, that same chromosome region in humans has been mapped in certain patients with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Alnemri notes. “We tested a few of these Parkinson’s samples but we did not find mutations in Omi. We still don’t know if this gene is mutated in other types of Parkinson’s or different neurodegenerative disorders.”

“Based on the severe neurodegeneration and muscle wasting in the mnd2 mouse, we will now begin to screen DNA samples from patients with related disorders in order to determine the medical impact of mutations in this gene,” says Dr. Meisler. “The prospects for treatment will be improved by accurate diagnosis in affected patients. We will extend the mutation search to the human gene, in order to determine its role in neuromuscular diseases.”

The Omi protein and related proteins are found in all organisms, including bacteria. In the latter, Omi-related proteins function as “molecular sensors” of cellular stresses, Dr. Alnemri says.

“Our next step is to find out whether Omi in humans functions as a sensor of mitochondrial stress and to understand at the molecular level how Omi regulates mitochondrial function,” he says.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.jeffersonhospital.org/news/e3front.dll?durki=17158All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

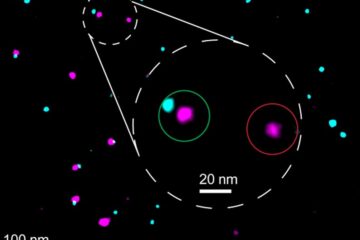

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…