Endostatin also effective on head and neck cancers

Susan Mallery

Researchers at Ohio State found that endostatin has a dual effect on head and neck cancer cells – the compound prevented the cells from developing new blood vessels and also hindered the mechanism cancer cells use to migrate throughout the body and invade other tissues.

Head and neck cancers originate on the epithelium – the layer of tissue covering the outermost surfaces of the body, including the skin and mucus membranes. Kaposi’s sarcoma tumors arise from the endothelium, the cells that line blood vessels.

“The vast majority of endostatin studies have concentrated on endostatin’s effects against endothelial cells, and haven’t focused on the drug’s anti-tumorigenic possibilities,” said Susan Mallery, the study’s lead author and a professor in the Ohio State College of Dentistry’s department of oral and maxillofacial surgery and pathology.

“We wanted to explore other options for endostatin use,” she said.

After getting promising laboratory results with treating oral cavity tumor cells taken from men with oral cancer with endostatin, Mallery is suggesting the possibility of an implanted drug delivery system, one that could deliver endostatin directly to the site of a tumor after it was surgically removed.

“About half of all people with head and neck cancers die as a result of local disease recurrence,” Mallery said, adding that such cancers account for about 7 percent of all cancers in the United States. “Another major concern is patient compliance with follow-up treatment after the original tumor is removed.

“It’s possible that one day doctors could treat these patients with an implanted delivery device that dispenses a sustained, therapeutic drug concentration right where it is needed the most – where the tumor was,” she continued. “Such a treatment option not only provides a constant therapeutic drug level, it also eliminates concerns regarding patient compliance.”

In the current study, endostatin treatment reduced by half the number of invasive head and neck cancer cells, and also reduced the number of cells capable of migration by one-quarter. Migrating cells receive some sort of chemical signal before moving in a directed fashion throughout the body. Invasive cells migrate, but they also produce an enzyme that actually digests the membranes of the cells they’re trying to take over.

The research appears in a recent issue of the journal Anticancer Research.

Mallery and her colleagues received funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and from the Ohio Division of the American Cancer Society.

Contact: Susan Mallery, (614) 292 5892; Mallery.1@osu.edu

Written by Holly Wagner, (614) 292-8310; Wagner.235@osu.edu

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

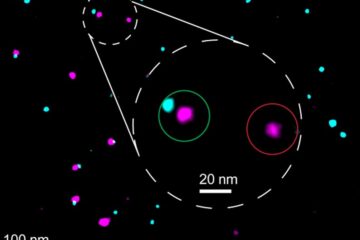

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…